- Tony Fouhse

- Rachel Eagen

- Steve McOrmond

- Donnez Cardoza

- Jolene Armstrong

- Bob Bickford

- Jared Joslin

- Jim Diorio

- Kathryn McLeod

- Chris Robinson

- Rebecca Blissett

- Rachelle Maynard

- Rebecca Abbott

- K. McLeod

- Innes Welbourne

- Chris Vaughan

- Cinemascope

- Molly Dario

- Visit Wuhan

- Geoff Munsterman

- The Galaxy Brains

- Angela McFall

- Sacha Gabriel

- Jane Wilson

- Letters To The Editor

- Zachary Rombakis

- Nancy Friedland

Dickens might have been on to something when he populated his Christmas story with spirits visiting in the night, after all it’s the darkest time of year, a time when after the parties are over, and the visitors have gone home, we might reflect on our past year, and wonder what the year ahead might hold. We think that spirits prefer Samhain, but I think they like midwinter best.

It’s the second time in the last couple of weeks that I’ve been visited, haunted, this time, when, driving home from the grocery store, scanning through the radio stations for something good, the dial settled for just long enough for me to pick out the words “walk on part in a war” and my hand darted for the dial to pause it there. And immediately my heart ached with the yearning that accompanies the simplest of phrase: wish you were here. It’s a song that will always remind me, and conjure a series of memories, episodic, often sliding through my consciousness as a series of snapshots, sometimes as if it were 8mm, the film, starting to fade a little, the colours too lurid at times, too soft and disappearing at others. The music taps into that reservoir.

Martin.

Just yesterday, I found one of the many hand-written memos, my dear friend Martin used to send me in the mail when he hadn’t heard from me for while. Often they began with a hearty salutation in Old English, a quip from Beowulf,

|

Hwæt! Wé Gárdena in géardagum |

|

|

þéodcyninga þrym gefrúnon· |

|

|

hú ðá æþelingas ellen fremedon |

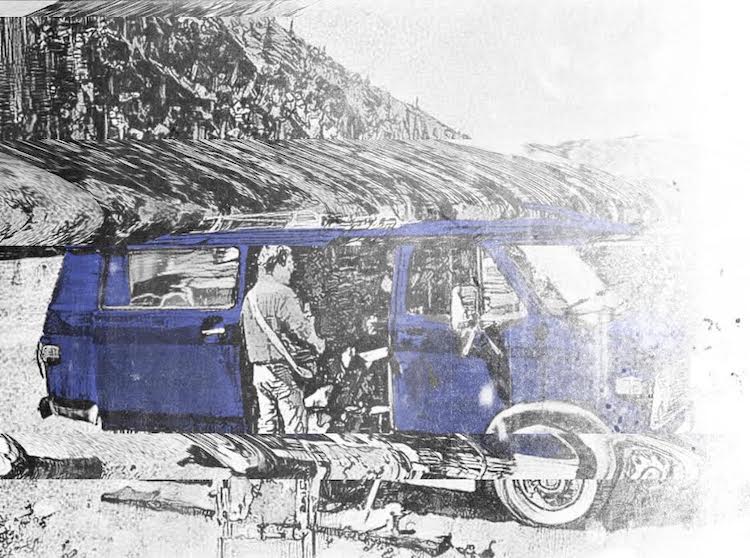

Which made sense since we met in an Old English class, in which, over the course of the two semesters we battle- axed, and Dane- bladed and quaked in the shadow of Grendel’s mother. I don’t know that we truly conquered the text, but our translation skills grew sharp, and we had a lot of laughs. Martin was using a wheelchair at this time, but he was still driving, his blue maximum boogie van, kitted out with hand controls, and a wheelchair ramp—you could hear it coming for 6 blocks–and when he arrived in class, he slid out of his wheel chair, and into the desk behind mine, never beside, so he could heckle me, unobserved by the prof, from behind my mass of unruly hair.

I remember one time, when he replied with a different line from a Pink Floyd song, or Beowulf, to everything I said. For at least an hour. Oddly, his responses almost made sense. Annoying, but it was the sort of game that Martin liked to play: word play, and cryptic reference to Leonard Cohen, and to time past. There was always nostalgia with Martin. It was a yearning for not necessarily better, easier times, but for times that could never be recaptured. He had a keen sense of finality.

I never really understood Pink Floyd, until Martin. For me, it was summers, not yet 10, playing at my friend’s house across the alley, listening to her significantly older brothers’ records, which we really weren’t supposed to be doing, because we were little and silly, and we might scratch them, these precious discs bought with the hard earned cash of teenage boys in the 1970s. But we did, and they were delicious morsels, tastes of a more grown life that we could only as of yet imagine. I remember Trooper, and the boys in the bright white sports car, waiving their arms in the air. And oh– The car was probably stolen…We pedalled through the neighbourhood shouting la lalala, la lalala la at the top of our lungs. And better yet, raise a little hell– which felt so taboo because it had a swear word in it, It was glorious to shout “raise a little hell”, arms waving in the air, heads banging, hair tussling about–and although we may not have fully appreciated what raising hell really meant, we knew it had something to do with creating mayhem and not caring. There was Chilliwack and Cheap Trick, and they were fun too, but the treasure in that stack was Pink Floyd. A double album we were for sure not supposed to touch. We’d skip over most of the songs and dive right into We don’t need no education. We don’t need no thought control. Finally. This. This spoke our language. This inspired mass rebellion. We didn’t know about The War, scarcity, hardship, and changing times, or generations pitted against each other. The only time we knew was our time, and we were all cut-offs, and tube tops, bikes and softball, bubble-gum and hockey cards. We thought we’d discovered the secret that would free us from the bonds of educational slavery, endless hours of school. We couldn’t shout these words loudly enough. We didn’t know what oppression was.

But my child’s view was that these songs were fun, silly, comedy even. And there ended my understanding, as I moved along, listening to the music of my day, all but forgotten. Until Martin, one afternoon evening night in Dewey’s, that smoked filled campus bar, packed beyond fire code capacity with sweaty students, tossing their rumpled bills on the pile for another pitcher of beer, the tinny breaths of new wave, post-punk, garage music, with a little classic rock thrown in, blaring over the speakers, everyone shouting, the floor, strewn with toques and parkas. However did we find our mittens backpacks textbooks when it was time to go home?

Martin, said, shouting at me above the rabble, “you have to listen to the whole album, all the way through, without stopping or talking.” “I don’t know if I can do that. Not talk, I mean,” I said. “I don’t know if you can either!” he said. And so we did, one day, months later, after the MS had reared its ugly head, and had come to excise more of Martin’s strength, and even though he’d been doing alright for a while, that year, his bones became fragile, and he broke his leg rolling over in bed. I stopped by his place to turn him, to get him stuff, to wheel him to the Dr. One day, upon returning him home after an x-ray, tired out from the heat and the extraordinarily uncomfortable way in which his leg had to be cast sticking straight out from his hip, we put on The Wall, and just sat and listened. I didn’t talk.

Years later, when the MS again made a forceful campaign to once and for all ravage his body, and he was no longer able to live on his own, I remember sitting with him. I was feeding him with Zute Drops (Martin was born in The Netherlands), he asked me to turn on some music, just anything. So, I grabbed a cd, Pink Floyd, but not The Wall. We grew quiet, he grew sleepy, and eventually, I left the hospital room on tiptoe so as not to wake him, but not before, I wept my way through, Wish You Were Here. It was one of the last times I’d see him.

I miss getting these memos that looked like they’d been scrawled by a mad man, that contained secret messages in a language hardly anyone can read. I miss those pitchers of beer, and crowded smoky days, overheating in winter clothes in a bar that doesn’t exist any more, listening to music, philosophizing, before we knew pain.

Shine on, you crazy diamond.

Jolene Armstrong

Jolene had always wanted to be a firefighter, but somehow ended up a professor of literature with a creative writing habit. She likes to collect odd, beautiful, shiny things and people. In her spare time, she assembles in images and words the shimmering ephemeral beauty that marks our collective existence on this blue planet. She lives and works in the boreal forest.