- Bob Bickford

- Michael Murray

- David Barry

- P.D. Cardoza

- Robin Gadient

- Yael Friedman

- Kay Murcer

- Corey Hardeman

- Bart Gazzola

- Donnez Cardoza & Bob Bickford

- Chris Robinson

- Kathryn McLeod

- Roberta Rainwater

- Jon Flick

- Clayton Texas East

- Winnie Ramsdell

- Lisa McIvor

- Dale Synnett-Caron

- Lynsey Howell

- Susan Birchenall Gates

- Michael Murray

Chris Robinson

Lviv, Ukraine

Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

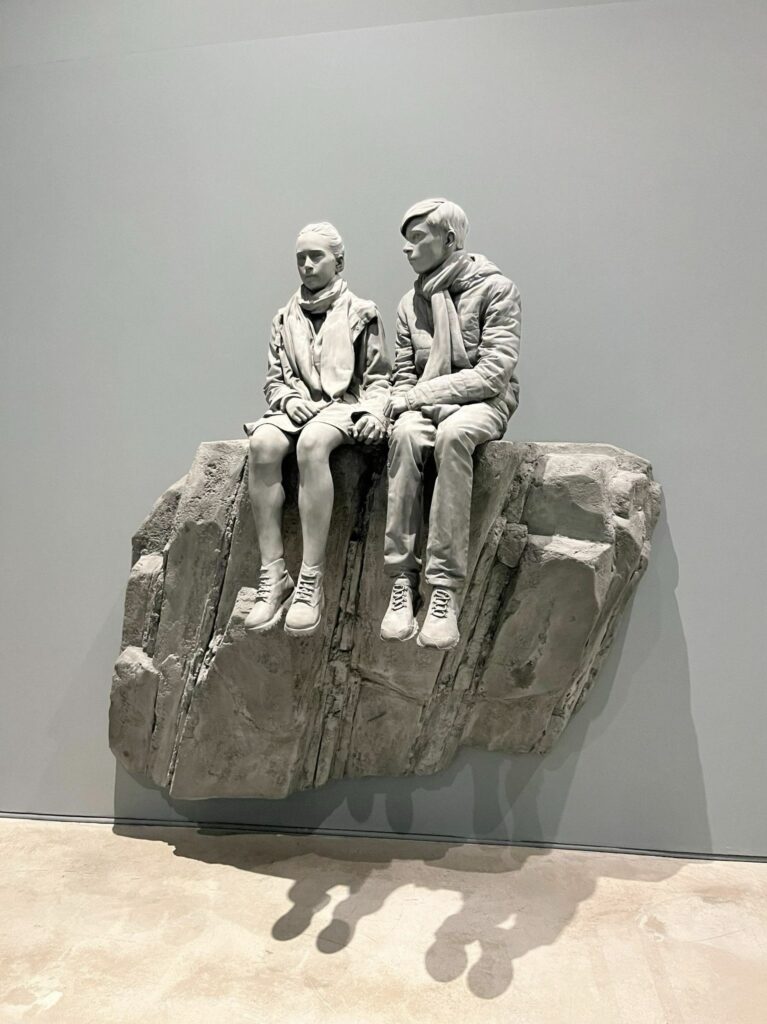

The Cliff by Hans Op de beeck

Love in Times of Chaos

Zagreb, Croatia, 2022. I was there because I couldn’t attend the animation festival in 2020 to accept an award due to the pandemic. She was there from Ukraine, in temporary exile following Russia’s February invasion.

Our first meeting didn’t go well. I was being interviewed about a new book I had written during a public event. The moderator was terrible—she had clearly not read the books and asked the most superficial questions. At one point, she even criticized me for there not being enough women in the book—which she hadn’t read. If she had, she’d have seen that she was wrong. What’s more, I was a guest. You don’t attack someone you’ve invited.

I was furious.

I turned my head toward the audience in blind rage. In my sightline was a woman with an equally sour expression. It made me even angrier, and out loud I said, “What’s with the bitchy look?” She responded that she felt my pain, but she was equally furious with me and wished me an early death. I felt something jolt me, like the sensation of being near a lightning strike. I had no idea what it was, but I brushed it aside and moved on.

After the event, I sought Lightning Girl out to profusely apologize. She was also a film festival director, running one in Kyiv. We spent that festival getting to know each other, and over the next couple of years, we learned bits and pieces about one another. There was no thought of anything beyond friendship—after all, we were each in relationships, living in different countries, and any spark was just the byproduct of meeting new people at an international event. It happens all the time. Besides, when we did meet at a couple of other festivals afterward, all we did was annoy each other.

Impossible.

Two years later, we became a couple.

By October 2024, I was preparing to head to Lviv, Ukraine. I was anxious, as were some of my friends and family, who probably thought I was crazy. I reassured them that Lviv was safe, comparing the front lines to being near Quebec City, and telling them Lviv would be like Vancouver. In hindsight, I realize I was off—Lviv is about 1,000 km from the front, so a better comparison would be Regina, not Quebec. But I had spoken to Lightning Girl almost daily and saw how normal her life was. There was little to worry about. Besides, she repeatedly told me just how safe it was in Lviv.

This is the artist’s studio I would rent for two months. Three weeks before I arrived the terrace door had been blown in after a missile hit residential buildings across the street, killing seven people, including a wife and her daughters. The father survived.

That’s what the street I lived on looked like in September 2024.

Yep. Perfectly safe.

Strangely, I wasn’t so freaked out; I thought the odds of an attack hitting the same area were pretty remote.

On October 1, 2024, Lightning Girl and I flew back together from Canada since she’d attended our festival in Ottawa. Unable to fly directly to Ukraine, we had to go to Kraków, Poland, and then drive about four hours to Lviv, including an hour or two waiting at the border (I’ll spare you my rant about the Polish–Ukrainian system—Canada’s actually seems efficient by comparison).

Our first night was spent at her house, where I heard my first air‑raid siren. As I soon learned, whenever a Russian MiG enters any part of Ukrainian airspace, sirens sound across the country—even hundreds of kilometres from Lviv. Being new to it all, I was more than mildly anxious. Jet lag and a bad cold didn’t help, and I barely slept during my first week.

About a week later, we took the train to Kyiv. Although the city endured frequent drone attacks, it carried on almost as if nothing had changed. I was amazed that the train not only ran but was always on time—meanwhile, Canada’s Via Rail never is, crawling along at carlike speeds. Over time, I learned just how resilient Ukrainians are: every service except flights continued to run efficiently. Canadian services could learn a lot from Ukraine.

So… on my first night in Kyiv, I collapsed into a deep sleep. Suddenly, a loud voice startled me: “CORRIDOR NOW!” I stumbled out of bed, still in a fog, forcing myself downstairs. There was a Russian drone nearby, visible from our terrace.

My anxiety spiked. Was this a mistake? What the hell was I doing? Was I stupid, chasing love into a war zone? What about my sons? My Job? What if I died here? They’d unfairly blame her.

Photos of the damaged buildings across the street from where I was living in October 2024

Eventually, calm returned. For the rest of our visit, our relationship blossomed. Away from the fantasy of festivals, we functioned as a solid, loving partnership. I began meeting new people, and the most common question was, “Why are you in Ukraine?” To which I usually replied, “Because I’m an idiot who fell in love.”

On weekends, Lightning Girl—who drives like a Formula 1 racer, shouting multilingual passages that would make Malcolm Tucker proud—showed me western Ukraine: Ivano‑Frankivsk, the Fortress of Tustan in the Carpathians, and Drohobych, Bruno Schulz’s birthplace (then part of Poland). I’m not recounting a lame tourist trip—the thing that struck me on those drives was the endless memorials in every village. There might not be missiles or drones overhead, but the war is everywhere, each fallen soldier commemorated with a banner bearing their photo and dates. It becomes overwhelming to process just how many lives this Russian brutality has claimed.

No visit hit me harder than to Lychakiv Cemetery in Lviv, the city’s central burial ground. We saw a man, grief-stricken, standing before a grave—it was the man whose wife and children had died in that September strike. But what shocked me most was what lay outside the gates: the Field of Mars, formerly a city park, now a growing expanse of makeshift memorials to soldiers killed in the invasion.

Field of Mars Park, 2011

Field of Mars Park, 2024

Aside from a bout of anxiety after Trump’s election—I’d feared an uptick in Russian attacks, though Lviv remained spared—I got used to the routine. It felt… abnormally normal. You learn to live around air‑raid sirens and missile warnings on Telegram. Between alarms, you wake, make breakfast, hit the gym, and work. Before long, my days in Lviv mirrored those in Ottawa.

Still, reminders of war were ever present in Lviv. On the mall treadmill I’d occasionally spot amputees walking and shopping. The city bristled with military‑recruitment billboards (I often mistook them for video‑game ads). There are military hospitals here, training grounds there, and young men and women in combat fatigues at every turn. I’d see them and wonder if they’d be alive a week later.

After a three-month return to Canada, I headed back to Ukraine in March 2025. I was calmer now, almost confident that Lviv would be spared anything more than the weekly MiG warnings.

In April, amid endless reports of ceasefires—each one seemingly different from the last—Russian attacks on civilians and civilian infrastructure increased. On the day Sumy was struck, killing 35 people, including children, we were strolling through the old town. It was one of the first mild days, so everyone was out. The centre buzzed with music, busy restaurants, shops, and bars. Young and old mingled; you’d never know there was a war, let alone that children were dying elsewhere in the country. I felt guilty. How could we shop and eat and carry on while missiles and drones were killing civilians and soldiers not far away? But what else can you do but live? “I can’t go on; I’ll go on.” That familiar, oft‑cited Samuel Beckett line fits perfectly here.

I came to see how little we truly grasp until we’re actually there—and even then, we barely glimpse the darker truths lurking in the shadows. Before arriving in Ukraine, everything I knew was filtered through the media’s lens. Now I recognize how misguided most outlets are, even those deemed “balanced,” like Al Jazeera or The Guardian. Every day brings another empty headline about Macron, Starmer, or Trump calling for an end to the war. Ceasefire talks dominate the airwaves, yet since they intensified, Russian missile and drone strikes have only increased. There isn’t a hint of peace to be found anywhere here.

And yet, there is love.

I’ve secured an apartment and expect to obtain temporary residency before the year’s end. At some point we’ll move in together, and I’ll continue shuttling between Ottawa and Lviv. The romance phase has evolved—as it always does—but our connection remains remarkably strong. We adapt, we carry on. Who knows how long or where this journey will take us, but I don’t regret a single moment.

Looking back, it seems inconceivable. We met solely because of two tragic events: my trip delayed two years by COVID, and her temporary escape from the early months of the war with a young child. I’m amazed how love can burst forth in the unlikeliest circumstances.

But then you ask yourself if you’d give up this love if it meant no invasion and no pandemic. The virtuous, compassionate part of me says I would—especially if it saved thousands of lives. I’m not a monster; I’m a decent human. Yet another part wonders if I really would. After all, I’m only human.

Fortunately, it’s a moot point: without those events, we never would have met—or at least not like this—and we wouldn’t have fallen in love. Our lives would have followed a different course, with new challenges and monsters lurking in the shadows, and perhaps new loves kindled or old ones rekindled—but none likely to match what we found—a place where the impossible became possible.

Chris Robinson

Chris Robinson is an animation, film, literature and sports writer, author of numerous books and Artistic Director of the Ottawa International Animation Festival (OIAF).[1] He also wrote the screenplay for the Jutra Award and Genie Award-winning animated documentary Lipsett Diaries, directed by Theodore Ushev. In 2020, Robinson was awarded for his Outstanding Contribution to Animation Studies by Animafest Zagreb.