- Tutu Kiladze

- K. McLeod

- Jim Diorio

- Grade Seven Girls

- Eliza Griffiths

- Alejandro Ballaudo

- LarchmontVanLonglunch

- Bob Bickford

- Michael McKinnell

- Tony Martins

- Gun Roze

- Carol Anne Gillis

- The Galaxy Brains

- Joe Macdonald

- Kathryn McLeod

- Rachel Eagen

- John Murray

- Zachary Rombakis

- Chris Robinson

- Ian Roy

- Jane Wilson

- Mr. Abbott

- Tracey Steer

- D. Rastgoo

- Robynne Sangiuliano

- Peter Simpson

- Alf Bogusky

- Michael Murray

- Yael Friedman

Not that long ago, while talking on the phone, I was asked how I was doing.

Somehow, the question caught me off guard. It was as if this was the first time since the pandemic started some twenty months ago that I actually had the mental space, the disposition, to sincerely consider the question. I sat down in my chair, sighed and stared blankly out the window.

I had no idea how I was doing.

I’d been on war footing for so long that the question barely even made sense. The pandemic, my doctors made clear to me, was an existential threat to which I was highly vulnerable. I imagined getting triaged on some concrete parking lot and then abandoned by the hospital staff for somebody with a better chance. The only thing that mattered was survival. I did not want our son to have to watch his father die, and then grow-up with that residual anger and sadness. Nothing else seemed relevant. We would do whatever it took to protect ourselves.

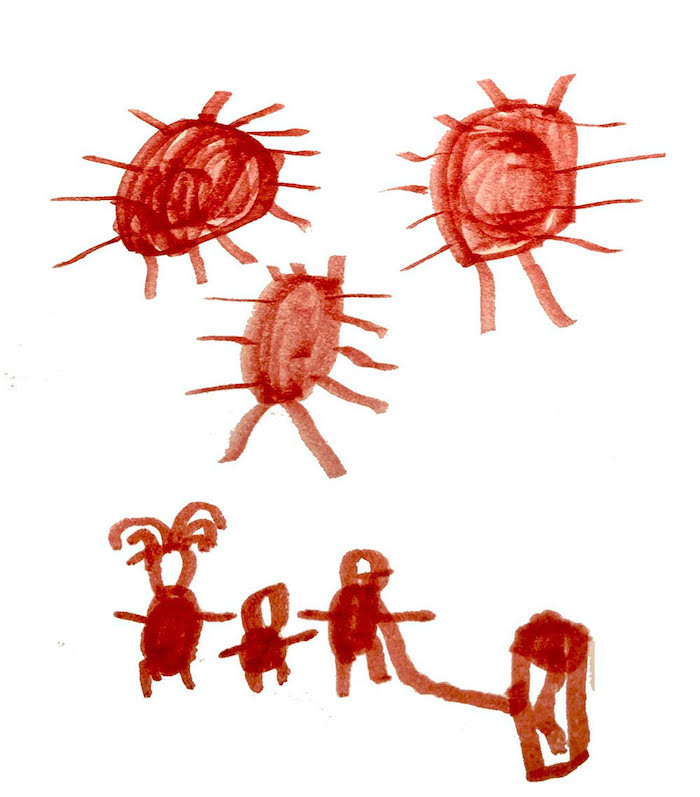

(Illustration by Jones Murray, aged 6. Rachelle has the spider leg hair, and I am attached by a tube to my oxygen concentrator, Jones bravely between us as we face the Covid monsters)

Before the virus became the gravitational force that all our lives orbited, images from China had already swamped my social media feeds. A video of a man falling dead in the middle of a busy city street. On another day, subway riders, cowering in the corner of a train while getting hosed down with some presumed disinfectant, and then occasionally, footage of a person bolting from the back of an ambulance only to be tracked down by faceless apparitions in hazmat suits.

Was this even true?

But it seemed a fire that couldn’t be put out. Like a great World War that kept pulling nation after nation into it’s maw.

I imagined ghosts massing on the horizon.

These mysterious forces that separated the lucky from the unlucky, watching, as they prepared to roll through us like an apocalyptic fog.

You couldn’t see Covid, of course, but still, it was utterly impossible to avoid it’s presence. It was the only story on the planet. It was everywhere, all the time, and it lived with us like an occupying army, altering and constricting the familiar margins of our lives. For most of us, it’s been a psychological trauma more than a physiological one. Paranoid, terrorized, disbelieving, whatever state we happened to find ourselves in, each one of us was called forth into a limbo where The Truth was impossible to ascertain– our leadership flickering, deteriorating like a broken hologram sent from the past. It was, I thought, a time to strip oneself of delusion. It was the time to become the person you actually were.

It was hard not to see it as a reckoning.

And of course, it’s been going on forever, this reckoning. Days we lived through rather than within. Time became a deep lake, a pool of drifting memories instead of a solid narrative connecting one milestone to the next. Overall, I had the depressive sense of being encased in amber—everything obscured, slow, inhibited. We held in our hearts souvenirs of a previous world, of biking home in the dark after an exciting party, all dreaming of the day we’d be released back into the golden shaft of light of our remembered lives.

But that’s the thing, isn’t it? You can’t step in the same river twice, and even if we felt we’d been frozen in place, mortality did not pause. The families we had been separated from continued to age, the lives of friends grew quiet then vanished, people fell ill to things other than Covid, foundational businesses collapsed. Our lives separated, reduced. Maybe this was a good thing, but most of us just felt dread and tension. For almost everybody I know, the pandemic has been a very difficult and sad time, for reasons obvious and obscure.

Jones, our four year-old son when all this started, was happy, throughout. In this obstructed, masked world of hand sanitizer, doomscrolling and irritability, he was happy. He danced. He played, he lit up our hearts. It may sound a little rich, that, but it is the truth. And he, still so close to the truth, was a light in a dark time—a portal through which the other world could shine through.

A week ago we took him to his first day of school. Grade one and it was a perfect blue morning. Jones was excited. He told us that he had a feeling in his stomach like when he goes on the roller coaster. Little bubbles rising within, hopeful and glad. I swear the boy sparkles. We passed through the Rosedale Valley Road, a green and golden tunnel, and Jones had brought shark teeth with him as he believed his class was going to capture a beaver on their first day. He was so excited about making friends, about his new shoes and yellow backpack, the pizza roll his mother made for him in his lunch. He was so ready, so confident, so full of high-fives. He was stepping into the world and he was not afraid, and it was the proudest moment in my life.

Truly, my cup runneth over.

The pandemic gave me that, too. It was the route we took to get to that radiant point.

There comes a time when you realize you’re no longer the central character in the story of your own life. Perhaps this is obvious to everyone, but there are things of much greater importance than the small ambitions we carry through our days. And so it goes. Because of the pandemic we lived as one entity, doing everything together for nearly two years, and to experience that sort of intimacy with my wife and son is something I can’t wish away. When I am asked how I am doing, the stripped to its essence truth is that if Jones and Rachelle are doing well, if they are standing in the sun, then I am, too.

The other night we went out for dinner. There was a tornado warning in effect, but we didn’t even blink at this threat. Off we went to some courtyard in the business district. All around us tall buildings, and in the middle a big fountain. The sound of running water as a warm, heavy wind ricochetted about us. It was so different it felt like we were on vacation in the tropics. Rachelle was beautiful and strong, and Jones was dancing, always dancing. He sees the moon in the sky, then a star. I tell him he should wish on the star and he does. He wants a rainbow lollipop. And it is dusk now, almost dark, and he runs off into the sloping cathedral light of the surrounding buildings, and runs a happy lap or two around the fountain, and then follows his mother as we all head back.

All of us so very lucky.

Michael Murray

Michael Murray is nothing without his wife.

Rachelle Maynard. That’s his wife.

Rachelle Maynard is the bomb.

She is the Galaxy Brain, and everything you see here is because of her.

That is the Capital T, truth.

But never mind that, for Michael Murray is truly the Galaxy Brain. He has won the New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest and is so good-natured that he was once mistaken for a missionary while strolling the streets of a small Cuban town. He has written for the National Post, the Globe and Mail, the Ottawa Citizen, Hazlitt Magazine, CBC Radio, Reader’s Digest and thousands of other prestigious publications and high-flying companies that pay obscene sums of money .You should buy his book, A Van Full of Girls and throw money at Galaxy Brain.