- Michael Harrington

- Alana Solomon

- Kathryn McLeod

- Rebecca Blissett

- Shane Redstar

- Bob Bickford

- LarchmontVanLonglunch

- Steve and Lily Harris

- Donnez Cardoza

- Delaney Turner

- Rachel Eagen

- Elizabeth Hodgson

- David Eddie

- David Himel

- Wil Abbott

- The Galaxy Brains

- Esther Pearl Watson

- D. Himel

- Terry Maynard

- David O’Meara

- Gun Roze

- Kayla Alle

- Jane Wilson

- Michael Murray

- Mr. Abbott & Dom Psd

- Peter Simpson

- Jeffrey Mackie

- Alf Bogusky

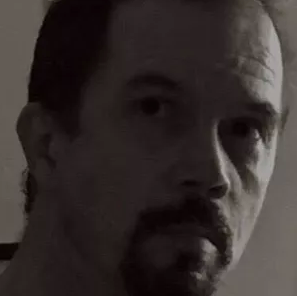

Bob Bickford

When I was little the library was my favorite place.I was born in Lone Pine, California. My parents liked to move and so did I, for a while. I have roots throughout the United States, but I was mostly raised in Toronto, Canada.

My father was a psychiatric social worker who grew up in the slums of Boston. He was a tough guy who got an education on the GI bill and pulled himself out of his birthright. He married twice, the first time to a woman who left him a widower. Alone with a toddler, I suppose he was determined that it wouldn’t happen to him again, because the second time he married a woman much younger than he was.

She was the product of a Southern family; royalty that included the same Duke family that bought a university and named it after itself. Wilful and rebellious, she scorned Southern convention, rejected the closeted skeletons and wide streak of alcoholism that hid behind decorated formality. She disowned her family, converted to Catholicism, marched for civil rights, and married the older man from a poverty-stricken background. I am the oldest of the seven children she bore, one after the next.

We were brought up in curious contrasts. There were the economies that so many mouths to feed on a middle class income made necessary; (hand-me-down clothes, Tang and powdered milk, peanut butter for ten thousand consecutive school lunches), but my mother’s background dictated private schools, music and dance and art lessons.

I attended St. Michael’s Choir School and studied piano and organ at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto. I hated studying anything at all; my mother was determined that I should be a doctor and despaired over my future. I only wanted to read fiction, and did so endlessly. The library was my favorite, enchanted place (it still is). I didn’t realize I was in fact studying for what I wanted to do most.

My father’s plan to not be widowed again fell through, and my mother was suddenly gone when I was 16. He had been ill equipped to raise one child the first time, and now there were eight of them; the youngest only three years old. In some sense we lost him, too.

Life changed, just like that. My behavior guaranteed me a quick expulsion from my exclusive school. I did manage a high school diploma (by the skin of my teeth) but I was mostly happy to leave school for good. I lost an early love, and wandered to Los Angeles. I learned about the streets, and about living in the places that cause most people to lock their car doors when they drive through. I was blessed with the same genes that took my father through life in the mean part of Boston, and survived.

Eventually, I grew up and moved again, first to Atlanta and then back to Canada. I made a living in the ‘fixing cars’ arena. I live in a very old house on a wooded lot that is infested by dogs and turtles and parrots, and perhaps the ghost of a young girl. My teen-aged son is a light in my life who wants to be an author and a professional football player. I never tell him that both are nearly impossible, because they aren’t.

The library has continued to haunt me. When age said the possibility of a university degree was long past, I decided to try my hand at a novel anyway. Somehow I finished it, and have produced one a year since. I’m working on my tenth.

You can visit Bob’s Blog HERE.

You can buy Bob’s many books HERE.