- Michael Harrington

- Alana Solomon

- Kathryn McLeod

- Rebecca Blissett

- Shane Redstar

- Bob Bickford

- LarchmontVanLonglunch

- Steve and Lily Harris

- Donnez Cardoza

- Delaney Turner

- Rachel Eagen

- Elizabeth Hodgson

- David Eddie

- David Himel

- Wil Abbott

- The Galaxy Brains

- Esther Pearl Watson

- D. Himel

- Terry Maynard

- David O’Meara

- Gun Roze

- Kayla Alle

- Jane Wilson

- Michael Murray

- Mr. Abbott & Dom Psd

- Peter Simpson

- Jeffrey Mackie

- Alf Bogusky

Ask The Galaxy Brains

Each lunar cycle, a human will be allowed to ask The Galaxy Brains a question. In this session, the human will have a choice of answers to consume from three different Galaxy Brains. Please send all questions, be they advice, desire for human-life coaching, knowledge of future or past, or merely interesting recipes, to mm@michaelmurray.ca.

HUMAN QUESTION:

Owls?

ANSWER #1 FROM GALAXY BRAIN PETER SIMPSON:

Owls.

Your question is concise. Owls will like that, for owls have no time for messing around. They’re fully booked being the coolest damned birds on the planet.

And that’s your question, right? Are owls, in fact, the coolest birds on the planet? My answer is, yes, hoot-hoot, hoo-hoo.

You might say, “Oh, but, dear and wise unpaid advice columnist, aren’t birds of prey like hawks and eagles the coolest birds on the planet?”

I understand why you’re confused because of that time when Gary Larsen drew a Far Side comic of hawks on a tree wearing sunglasses and one had headphones and a Walkman portable music player and the caption said, “Birds of prey know they’re cool.”

Well, here’s a fact that will blow your mind apart like a Pinto gas tank: Owls are birds of prey. Furthermore, while hawks and eagles sit around listening to music and wondering if their sunglasses are still hip, owls are out there being alert, mysterious and deadly. This is because owls are both cool and wise. Have you ever heard anyone refer to that “wise old hawk” or even a “really-quite-clever old eagle?” I didn’t think so.

Here’s another thing: Owls can turn their heads 270 degrees, which is far enough that it looks like the head is turning completely around like Linda Blair in The Exorcist. You can turn your head max 180 degrees, and that presumes you’re extraordinarily fit and flexible and not a modern flabby mess.

As if this argument is not already decisively settled, here’s another thing: Owls can fly in almost perfect silence. Compared to owls, stealth bombers are a brass band falling down a set of aluminum stairs and landing on a tin roof over a Metallica concert. Stealth bombers cost like a billion dollars each. Has an owl ever cost you money? I didn’t think so.

Owls fly so quietly that the people who build stealth bombers for the Air Force actually study them. Research into biomimicry want to know how owls fly so quietly that a big-eared mouse with exceptional hearing on the quietest forest day is just like, “Hot damn it’s a great day to be a big-eared mouse with exceptional hearing on the quie —” and BLAMMO!

You know where it’s not so great being a big-eared mouse with exceptional hearing? In an owl’s stomach. Because that’s where you are now, immodest mouse.

It’s your move, Air Force brainiacs.

HUMAN QUESTION:

Owls?

ANSWER #2 FROM GALAXY BRAIN JANE WILSON:

HUMAN QUESTION:

Owls?

ANSWER #3 FROM GALAXY BRAIN KATHRYN McLEOD:

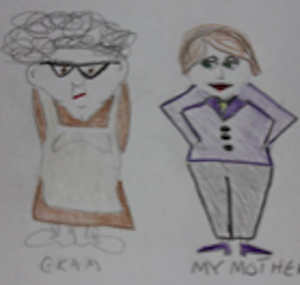

When I was four my father died and Gram came to live with us. She was my mother’s mother but my mother didn’t call her “mother”, she called her “Edna”. The reason for this was because Gram and Harold, my mother’s father, lived with Harold’s parents, and they acted as the parents of my mother and her siblings.

By the time our father died, Gram and Harold were divorced, Harold having run off with Bunny, adding eight more kids to the six he had with Gram.

It wasn’t an easy relationship between Gram and my mother. For one thing, my mother had been favoured by Harold, and vice versa, and although Gram and my mother were duty-bound, they weren’t at all compatible. My mother always going out, Gram staying in. My mother a doer while Gram liked to just sit and think.

Once when Gram was sitting in the kitchen, staring at the wall, I asked her what she was thinking. She said, “Nothing. I wasn’t thinking anything.”

It was said in the same chipper tone she said everything.

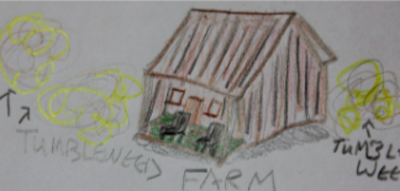

One thing my mother and Gram had in common though was that they both loved my Uncle Mac, the fourth born, and when he and my Aunt and cousins moved down the line to where my father had inherited an old farmhouse, my mother took to dropping Gram off there for the summer. In time, we would get dropped off there, too, but for a couple of weeks at a time, not the whole summer, and rarely all four of us, as both my older brother and sister did a month each at a summer camp near Espanola.

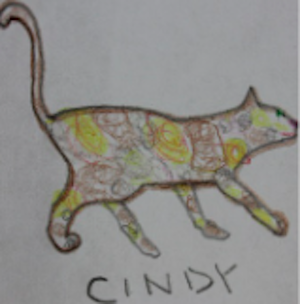

One summer, after being dropped off by my mother, who never stayed over at the farm no matter how much I wanted her to, we discovered that Cindy, a cat, had taken up residence. Unfortunately, we had Lucky, a spaniel/border collie from the humane society my mother got for my brother after our father died. Lucky was Cindy’s cue to disappear to the Chapman’s down the road, a working farm with water, which we didn’t have, returning to Gram and the farm once Lucky was back home in the Sault. Cindy did the same when we picked up Gram at the end of the summer.

I think it was the second year of Gram going to the farm for the summer, which she did earlier than the previous year because we were all still in school, that when we showed up on a Saturday with supplies – there were – kittens! Cindy had had kittens! Five adorable kittens!

You can imagine how exciting it was for us, five kittens to play with, name, possibly even bring home. But, of course, bringing them home was out of the question. Lucky wouldn’t tolerate one kitten, never mind five, but neither would my mother. And once my mother said no, that was it. No amount of pleading would change a no to a yes or even a maybe with my mother. No was the end of all hope. And no she wouldn’t be sad if I died of a broken heart because she wouldn’t have to listen to me whine about those damned kittens anymore.

Besides, Gram said the kittens were Cindy’s to look after, even though she’d already let us know Cindy wasn’t doing a good job of it.

“Now don’t get too attached to those kittens. They’re Cindy’s to look after, although I’m not sure Cindy’s much of a mother. She doesn’t seem very interested in them.”

This wasn’t at all what I wanted to hear. Even worse, Gram said the kittens were only in the farm living room while we were there because she didn’t want us mucking around in the back shed, where I’d already stepped on a rusty nail. Once we left, back they would go to the shed. Cindy was a barn cat, not a house cat, and so too her kittens. Not only that but it wasn’t like my mother was going to spend every Saturday driving down to the farm and back just so we could see kittens we weren’t supposed to get attached to.

Like I said, no amount of pleading ever changed a no to a yes with my mother and it was a couple of weeks at least before she drove us back down to the farm to see the kittens. This time, instead of five kittens, there were only three, and Gram said whenever she checked on them, Cindy wasn’t in the shed.

“Cindy may just be out hunting. But I think when she goes out hunting, that owl does some hunting of his own.”

Well I’m sure you can imagine the hue and cry that fell on deaf ears with that one. Oh how we pleaded with Gram to let the kittens back into the living room. I think she may have said something about the owl probably having had his fill, just to mollify us a bit, but we weren’t fooled, and indeed the next time we got back to the farm, the remaining three kittens were gone.

And no, Gram didn’t try to convince us they’d moved on of their own accord.

“I think that owl took those kittens one by one. And if you were to ask me, Cindy seems pretty darned relieved to have them gone. She’s even been spending more time in the kitchen with me, although she still stays out all night, hunting.”

Later, because my mother was more in tune with our sensibilities than was Gram, she said, “You know, it’s likely that owl was a mother, too, and needed to feed her children. And it’s a lot harder to be a mother owl than it is to be a kitten. Those kittens were just going to get big and be barn cats down the road and kill baby birds. Your Grandmother does enough around here. The farm is her vacation. Stop bugging her about those damned kittens.”

And we did. Eventually. And eventually too Uncle Mac moved and we were not wanting to spend so long at the farm with Gram. Finally, after a particular visit with Gram at the farm, I said to our mother, “I don’t think we should leave Gram alone at the farm anymore.” My mother reluctantly agreed, even though she didn’t need Gram living with us and probably didn’t want her to either. Later still, when Gram went to visit her much younger daughter in Peterborough, and just my younger sister was still living at home, my mother phoned me in Toronto, “Gram’s been staying with Sandra for quite a while now and gives no indication of when she’s coming home.” And with the confidence of a young person not overly concerned with the lives of mothers or grandmothers, I said, “She’s not coming back to the Sault. Send her trunk. She wants to live with Sandra now.”

And so my mother did just that and Gram never returned to the Sault and instead lived out her days where she began them, in Peterborough, with just one young granddaughter to mind, and Fred, Sandra’s partner, who was better to Gram than any of the rest of us had ever been.

Oh and somewhere in there, my Uncle Gordon, my father’s youngest brother and a bachelor to the end, having had one too many scotches on a Christmas visit, remarked after a re-telling of the kitten story, “You know, I met some of your mother’s line at your parents’ wedding, and I have to say, I think your grandmother might have been the owl.”

The Galaxy Brains

Jane Michelle Wilson, who, over the course of her life has actually been a professional advice-giver. (As The Advice Lady in the National Post and Janereaction in The Toronto Star.) Nowadays she gives her advice – solicited or un – privately.

One terrible night in 1984 she asked a non-pregnant woman when her baby was due. The horror of that moment lives with her still and she has never forgotten it. She thinks some worries are useful lessons, but most are just crap.