- Michael Harrington

- Alana Solomon

- Kathryn McLeod

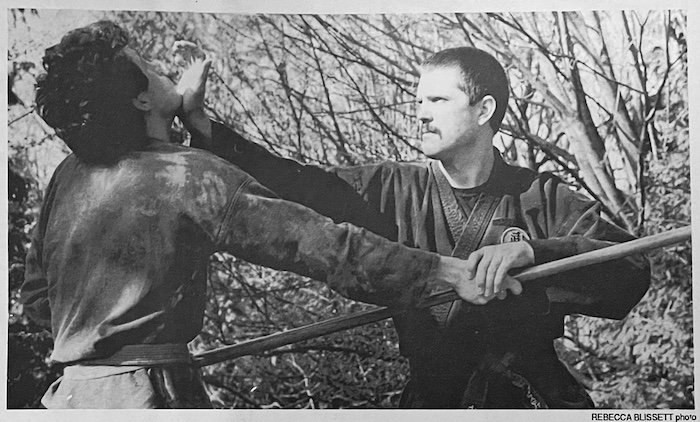

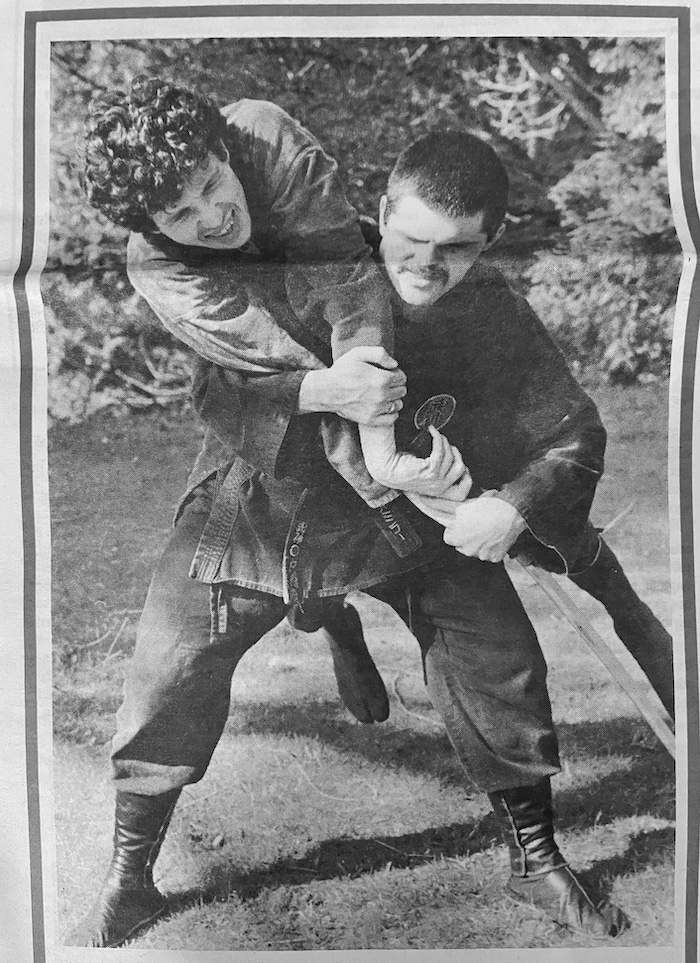

- Rebecca Blissett

- Shane Redstar

- Bob Bickford

- LarchmontVanLonglunch

- Steve and Lily Harris

- Donnez Cardoza

- Delaney Turner

- Rachel Eagen

- Elizabeth Hodgson

- David Eddie

- David Himel

- Wil Abbott

- The Galaxy Brains

- Esther Pearl Watson

- D. Himel

- Terry Maynard

- David O’Meara

- Gun Roze

- Kayla Alle

- Jane Wilson

- Michael Murray

- Mr. Abbott & Dom Psd

- Peter Simpson

- Jeffrey Mackie

- Alf Bogusky

Taekwondo totally sucks in a fight, you know.

My brother demonstrated one of the martial art forms, over-exaggerating snappy high kicks and stiff-armed low blocks. He got his junior black belt in taekwondo when he was just 12 so his movements didn’t even look that silly. But he sure made me feel silly, watching this reflection of clownery as he pretended to fend off invisible attackers one at a time.

See? He said. A joke.

I figured he knew what he was talking about. My brother had been in fights, usually winning by picking them. He lived for action TV and combat video games. It wasn’t a surprise that he wanted to check out a brand new ninjutsu school in town, but it was a surprise that he wanted me to go with him. Our relationship was built on boiling cross-eyed fury: instigation, agitation, provocation, punches. But he was 15, and I was 16 and had a car.

The ninjutsu school was held in a local park. Being a teenager, I’d assumed classes were held outside because of the natural elements; towering trees were targets for metal throwing stars, the steep ravine was practice for rappelling, the uneven ground covered in noisy twigs and leaves provided a test of stealth (heel hits the ground first and then slowly roll the outside of your foot to the toe). I eventually clued in that we were outside, hoodies under our gi tops in the cold weather, because the outdoors was free; the instructor had no dough for a dojo.

Bujinkan Kiri Ryu Dojo was run by a British man with a horseshoe moustache he liked to use to full effect by waggling it while unnecessarily staring you down.

Even though he told us he was a judo master, having studied during his time with the Royal Marines, he mostly wanted us to focus on deflecting punches and kicks with a slight twist of the hips. We’d obediently line up in our black gis, waiting our turn to dodge a bamboo sword the instructor swung down over us, landing blows with a loud thwack!

Sometimes he was nice, and he’d lay the sword on your shoulder, waggle his moustache, and let out a guttural hahahah before sending you back to the line. Often, though, he wasn’t, and that bamboo stick cracked down on the top of your head. Yelping wasn’t allowed – noise was deadly for ninjas! – but it wasn’t a quiet practice as that bamboo sword rattled like cheap window blinds.

It still hadn’t been revealed to me how being hit across the head with a bamboo stick or any of the other rituals, including moving our fingers through different configurations like ninja gang signs Earth! Wind! Fire! Water! Void! at the beginning of every class was going to make me better fighter. But I kept showing up. I even wrote about ninjutsu for my school newspaper. A genuine martial art, I’d written, sounding a little defensive.

Our fellow ninjas mainly were much older than my brother and me. The group included our neighbor who left his wife and kids for a fellow ninja lady – kunoichi –, a man with a fuzzy grey ponytail who told me that he’d like to take me travelling to places I could only dream of in his VW bus one day, and another guy who once sat my brother and I down to inform us that he was ready to die because he was going to be reincarnated as an eagle. There were two guys a year older than me, which represents a lot of presumed worldliness for a teenaged girl until it was later discovered that one of them used to spend his time practicing his roundhouse kicks behind the local Esso station at night.

One night, our group in the park received a visitor. He was a short, pudgy man with a messy bowl cut. He didn’t say anything, just reached into his ninjutsu gi, pulled out a piece of paper, handed it to our instructor and walked away. The adults of the group huddled and whispered.

A Japanese death threat, I heard. A Japanese death threat! What? On the drive home, my brother filled me in. Charles Scott. He teaches ninjutsu, and he’s a white supremacist leader. He said he was going to kill all of us.

For all the throwing star chucking, bamboo smashing over the head, and all the grand claims made about the power and responsibility of being a practitioner of the ninja arts, and that guy – clearly not a good guy – just got to walk away, unchallenged without even a single word.

Yeah, clearly a martial art that would help win fights.

Rebecca Blissett is a Canadian writer and photographer. This excerpt is from her forthcoming book Fused.

Rebecca Blissett

Rebecca Blissett enjoys karate, fashion, revenge.

Twitter @rebeccablissett

This excerpt is from her forthcoming book Fused.