- Lavely Miller

- Douglas Mason

- Corey Hardeman

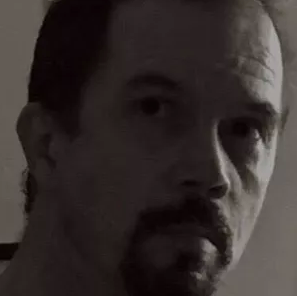

- Bob Bickford

- Rosby McCaul

- Diane Beckett

- Chris Robinson

- Tony Martins

- Rob Balcer

- David Himel

- Stephen Peck

- Douglas Mason3

- Elizabeth Hodgson

- Todd Dixon

- Hannah Brown

- K. McLeod

- Gun Roze

- Anonymous

- Sacha Gabriel

- Sean Singer

- Rebecca Blissett

- Dave Cooper

- Jeffrey Mackie

- Douglas Mason2

- rob mclennan

- Donnez Cardoza

- Michael Murray

- Rachelle Maynard

- Jane Wilson

- Alejandro Ballaudo

- Kathryn McLeod

- Jack Neary

- Alf Bogusky

Dear Ghost,

I get tired earlier in the evenings, now.

That’s the gentle part about getting old. The yawns creep up, the kind that shudder and creak the corners of my jaw, the kind that take me back to being little. Brush teeth, spit aqua-colored Crest, hand cupped under the faucet. Tap water tastes like clean-nothing these days. I miss the metal taste from the bathroom faucet—it always echoed summer nights, a reminisce about garden hoses.

There’s nothing on earth beats a day that makes me squint, green grass, and a mouthful of July water from the hose. The spigot is painted red and it spin-squeaks open, one-two-three twists. Wait while the water runs, first hot from the sun and then suddenly ice cold. Heaven splashes my face wet, my mouth awkward as a first kiss, water spilling past onto the lawn, more goodness than I can take in.

The grass is soaked, spongy cool beneath bare feet, reflecting blue, enough loveliness for the whole world. If I left here with no more than the taste of hose water in my mouth, it would be enough.

Clock says eight. Outside the window, the sky deepens but hangs onto blue until the last second before dark. July is so perfect the blue doesn’t want to go.

Good-nights, and my mom curled reading a book, her bare feet tucked beneath her. Her eyes follow me out of the room. My dad lifts his glass in my direction without looking away from the teevee, a toast he isn’t aware of making.

The light from the hallway falls across the floor to my bed, a sidewalk to the moon. An electric fan swivels back-and-forth, back-and-forth, in front of the open window. A cloud of moths moves across the streetlight on the corner. The night outside hums with its own business, sweet living creatures I never see during the day.

Nighttime is when the gentle things come out. The dark is where they’re safe.

The sheets are blessed cool, a little rough from drying on the line. The clean smell says my mom loves me even if I’m too old to kiss, and summer will never end. I can put my feet on the pillow to steal a little reading from the hall light, but I’m too tired. The fan rattles as it blows breezes from faraway across my forehead and cheeks.

My pillow and drifting—there are planes to fly, bikes to race, bat-crack singles to line over the second baseman’s glove. Mostly, there’s the little girl who sits at the front of the class to rescue from dragons and fires, bank robbers and rushing locomotives, all sorts of peril and trouble and upset. I started wearing glasses in grade two, but I never need them when I save her. I don’t wear them in dreams.

Dreams now, staring into the dark, to take me into dreams.

When I’m gone from here, the moths will still swirl in the streetlight and the gentle creatures beyond the window will go on about their lives. Downstairs, my mom will still turn soft pages and the ice cubes in my dad’s drink will chime when he sets down his glass. A two-tone Impala will coast to the curb outside, dropping off the young woman who lives across the street. She’s too old to rescue from bank robbers, but she always shows me a sweet smile and a wave. I hope her dreams come true.

You were my best dream, ghost. The others were practice. I didn’t save you from all your dragons, and I didn’t always get there in time when you needed help. I’m sorry about that, but you were pretty good at fighting dragons by yourself. Sometimes, you just let me think I helped. You were always kind.

In the end, I think we saved each other. That stands, and that’s probably enough.

Yawns are nothing to be afraid of, you whisper. Taste the water.

Sweet dreams.

(Love, Ghost: Letters from Sunset and Vine)

Bob Bickford

When I was little the library was my favorite place.I was born in Lone Pine, California. My parents liked to move and so did I, for a while. I have roots throughout the United States, but I was mostly raised in Toronto, Canada.

My father was a psychiatric social worker who grew up in the slums of Boston. He was a tough guy who got an education on the GI bill and pulled himself out of his birthright. He married twice, the first time to a woman who left him a widower. Alone with a toddler, I suppose he was determined that it wouldn’t happen to him again, because the second time he married a woman much younger than he was.

She was the product of a Southern family; royalty that included the same Duke family that bought a university and named it after itself. Wilful and rebellious, she scorned Southern convention, rejected the closeted skeletons and wide streak of alcoholism that hid behind decorated formality. She disowned her family, converted to Catholicism, marched for civil rights, and married the older man from a poverty-stricken background. I am the oldest of the seven children she bore, one after the next.

We were brought up in curious contrasts. There were the economies that so many mouths to feed on a middle class income made necessary; (hand-me-down clothes, Tang and powdered milk, peanut butter for ten thousand consecutive school lunches), but my mother’s background dictated private schools, music and dance and art lessons.

I attended St. Michael’s Choir School and studied piano and organ at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto. I hated studying anything at all; my mother was determined that I should be a doctor and despaired over my future. I only wanted to read fiction, and did so endlessly. The library was my favorite, enchanted place (it still is). I didn’t realize I was in fact studying for what I wanted to do most.

My father’s plan to not be widowed again fell through, and my mother was suddenly gone when I was 16. He had been ill equipped to raise one child the first time, and now there were eight of them; the youngest only three years old. In some sense we lost him, too.

Life changed, just like that. My behavior guaranteed me a quick expulsion from my exclusive school. I did manage a high school diploma (by the skin of my teeth) but I was mostly happy to leave school for good. I lost an early love, and wandered to Los Angeles. I learned about the streets, and about living in the places that cause most people to lock their car doors when they drive through. I was blessed with the same genes that took my father through life in the mean part of Boston, and survived.

Eventually, I grew up and moved again, first to Atlanta and then back to Canada. I made a living in the ‘fixing cars’ arena. I live in a very old house on a wooded lot that is infested by dogs and turtles and parrots, and perhaps the ghost of a young girl. My teen-aged son is a light in my life who wants to be an author and a professional football player. I never tell him that both are nearly impossible, because they aren’t.

The library has continued to haunt me. When age said the possibility of a university degree was long past, I decided to try my hand at a novel anyway. Somehow I finished it, and have produced one a year since. I’m working on my tenth.

You can visit Bob’s Blog HERE.

You can buy Bob’s many books HERE.