- Lavely Miller

- Douglas Mason

- Corey Hardeman

- Bob Bickford

- Rosby McCaul

- Diane Beckett

- Chris Robinson

- Tony Martins

- Rob Balcer

- David Himel

- Stephen Peck

- Douglas Mason3

- Elizabeth Hodgson

- Todd Dixon

- Hannah Brown

- K. McLeod

- Gun Roze

- Anonymous

- Sacha Gabriel

- Sean Singer

- Rebecca Blissett

- Dave Cooper

- Jeffrey Mackie

- Douglas Mason2

- rob mclennan

- Donnez Cardoza

- Michael Murray

- Rachelle Maynard

- Jane Wilson

- Alejandro Ballaudo

- Kathryn McLeod

- Jack Neary

- Alf Bogusky

Celebrating Sean and the Spartans

These days, I’m feeling like an onion—a thing with layers upon layers upon layers—and sometimes when I peel one of them back, the act produces tears.

As a 55-year-old dad with a five-year-old son, I’m also enjoying many of those “first time” parenting moments, albeit at a more advanced age compared to your typical dad. Maybe that’s why I become more reflective when the moments arrive, something that can lead to a renewed appreciation for people in my past and, on occasion, a deeper understanding of myself.

In a few days time, for instance, I’ll take my son to a sporting goods store to help him choose his first pair of soccer shoes (or soccer “boots,” as those close to the sport would prefer.)

Rather than quickly order a pair online, I want this purchase to be a father-son ritual, a nascent rite of passage for the both of us, the significance of which will be lost on him but cherished by me.

Soccer, you see, and the relationships surrounding it, were foundational parts of my young life. The experiences from those years are “hard-wired into my brain” as my friend Noel Cunningham would say.

Noel was my earliest childhood chum and his father, Sean Cunningham, was our first and only soccer coach throughout our young lives. The Cunninghams lived directly across the street in my family’s suburban Toronto enclave. Every summer, Sean diligently guided our highly successful North York Spartans team, starting from the youngest “Squirt” division and right through our cusp-of-manhood high school years.

It was largely oblivious to us as kids, but for this guidance we were blessed. Sean was an excellent example of a what a coach can be: he was highly competitive and pushed the team toward excellence yet his motivational style was never mean-spirited or manipulative. The atmosphere around us was joyful and there were strong bonds among the parents, most of whom were immigrants to Canada from places all over the world.

Teasing Irish humour was central to Sean’s communication style. Even his harshest criticisms were salved with a conciliatory barb or perhaps an in-joke shared with the assistant coaches (who were all either Scots or Brits, so the jokes were free-flowing). The humour eased the sting because you felt that you were not being laughed at, you were being laughed with. You were also, critically, developing a thicker skin and learning that when bonding with a group of males you would almost ceaselessly poke fun at one another.

Sean’s way was not to become a father figure but as a coach he was a constant, an anchor, and was soft-hearted enough to know when to give emotional support. My most vivid memory of him is from a rare occasion when I was momentarily hurt on the playing field. An opponent had run across me and clipped my kneecap with his boot. I fell to the turf, crying in pain.

Sean sprinted out with the “magic sponge” medical kit that’s an honoured part of youth soccer culture: a plastic bucket containing nothing but water and a sponge. He attended to me with just the right blend of coaching sternness and friendly care. He squeezed the sponge’s magical waters over my knee, ruffled my hair, and quietly urged: “Don’t let them see the tears. Don’t let them see the tears.”

I cried a little longer anyway because I knew I would not be judged, and then gathered myself and rambled back into the fray.

( The early years. That’s me, the little punk standing next to Sean wearing his trademark red tracksuit.)

A tool and die maker

Sean was born in Dublin in 1944, where he grew up to be an excellent soccer player. Later he moved to England but didn’t quite catch on with the professional ranks.

When he left school, he began a tool and die maker apprenticeship and then

emigrated with his family to Toronto at the age of 18. After completing the apprenticeship, Sean eventually took up his trade at an on-the-rise firm called International Business Machines.

Despite his physical skills, the folks at IBM quickly saw that Sean was a natural leader, sent him through a management program, and promoted him to the mechanical engineering team. Next he moved into mechanical design and ended his career as head of that department.

After he’d married his wife Margaret (a Scot) and begun raising young Noel (a second son, Colin, would come later), Sean revived his passion for soccer by coaching.

Almost immediately, our side competed at the highest level and continued that way for a solid decade. Notably, for several years the team included two future NHL hockey players, Kirk McLean and Nick Kypreous.

The competitive pinnacle of it all may have been the team’s appearance one year in the final of the Metro Cup, a competition among all of Toronto’s top club sides. Thrillingly, the game was played on the Astroturf at Exhibition Stadium and was particularly memorable for me because I missed a penalty kick in the late stages that would have won us the trophy.

Throughout his time as our coach, Sean had entrusted me to take virtually every one of the team’s penalty kicks. If you know soccer, you know that this trust is no small matter. Penalty kicks may look easy but the pressure in these often decisive moments can be extraordinary.

Fortunately, I was usually good at facing up to the occasion and very rarely missed. I’d go entire seasons without missing, in fact. But this time, with the Metro Cup on the line, I’d blown it, and I remember to this day still in excruciating detail.

Stepping up to the biggest penalty of my life, the pressure was so great that I could not raise my head to look up at the goal. Instead, my optical field shrank to a kind of tunnel vision and I could focus only on the ball placed a few yards ahead of me until I heard the whistle, ran forward, and breathlessly kicked it.

With the shot’s path determined, the spell was broken. At last I looked up, just in time to see the ball skitter past the right post by a good two feet. Under a weight of responsibility far greater than anything I’d ever felt, I’d taken aim with pure guess work.

The game went into extra time and we eventually lost. That the history of soccer is littered with crucial penalty misses from the game’s biggest stars was, and is, of precious little consolation to me. The miss remains the single biggest gaffe of my life in sports. Of course Sean never reproached me for it, but I felt like I’d let him and the team down. And the memories remain, hard-wired into me.

A few years later, as high school ended, soccer slowly petered out. Many of us were gearing up for lives at college and university and it felt like we were solely focussed on the future. Years passed. Then more years. I moved away from Toronto and lost touch with most of the Spartans gang.

Reviving old feelings

Penalty kicks aside, there’s barely a handful of things in my history that I regret. Not attending Sean’s memorial is one of them.

He and Margaret retired to Victoria B.C. in 2007, joining Noel and his family there. But just 12 months later, Sean was diagnosed with cancer. It had aggressively spread to his brain and took him, far too early, in 2009.

By that time I had been living in Ottawa for eight years and felt quite disconnected from my soccer-playing youth. Perhaps there was a scheduling conflict to justify missing the memorial, but these days I also see how the physical distance from Toronto had led to a convenient emotional remove as well.

Historically, this has been my way. I’m not a bridge burner but I’m likely to let certain connections languish until they’re grown over with wild foliage and difficult to traverse. It has seemed easier to release emotional ties than to keep them adhered. I’ve told myself that I’m simply moving on—moving away—but inside there’s something more profound at work about being afraid to revisit old feelings … or possibly just being afraid to feel.

Now that I’m raising a son myself, the more I think about my years with Sean, the more I realize how fortunate I was to be around him and guided by him. I came into my own as an athlete and a young man under his sporting tutelage.

Thank you, Sean.

Those who say that youth is wasted on the young are yearning for a second go at the care-free years of pure exploration. But they overlook something. Those are actually the years when, just beyond our understanding, the iron-and-bone of who we are is formed.

No, youth is only ever wasted when ties to it are allowed to grow over with foliage, choking out opportunities to understand it and honour it.

In the Jung psychology process of self discovery called “individuation,” we are onions peeling back layers of ourselves to reveal deeper ones, closer to the core, even if we’ll never get all the way there.

( The final season. By now we had grown taller than the coach. I’m standing, far right.)

— With thanks to Margaret and Noel Cunningham

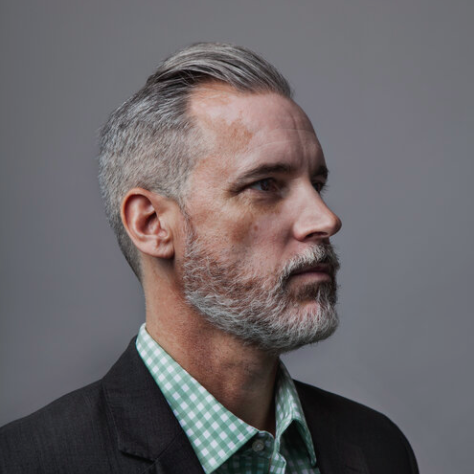

Tony Martins

http://tonymartinscreative.space

Tony Martins is a hearing-impaired childhood bed-wetter and three-time failer of the driver’s license road test. You could learn from him! He would happily accept anything donated by readers through the excellent Galaxy Brain site.