- Ravi Zupa

- Douglas Mason1

- Natalya Sukhonos

- Yael Friedman

- Jack Neary

- K. McLeod

- Bob Bickford

- Chris Vaughan

- Chris Robinson

- Lynn Crosbie

- Rosby Strong

- Alana Solomon

- Velvet Chic Volcano

- Douglas Mason

- Suzanne Richardson

- Steve McOrmond

- Charles Wing-Uexküll

- Corey Hardeman

- Eliška Jahelková

- Todd Dixon

- Donnez Cardoza

- Rebecca Blissett

- Lunar Boy from Salem and Cinemascope

- Douglas Mason2

- Gun Roze

- Jane Wilson

- Toby Rosenbloom

- James Sutherland-Smith

- Kathryn McLeod

- Michael Murray

- Josh Patterson

- Anonymous

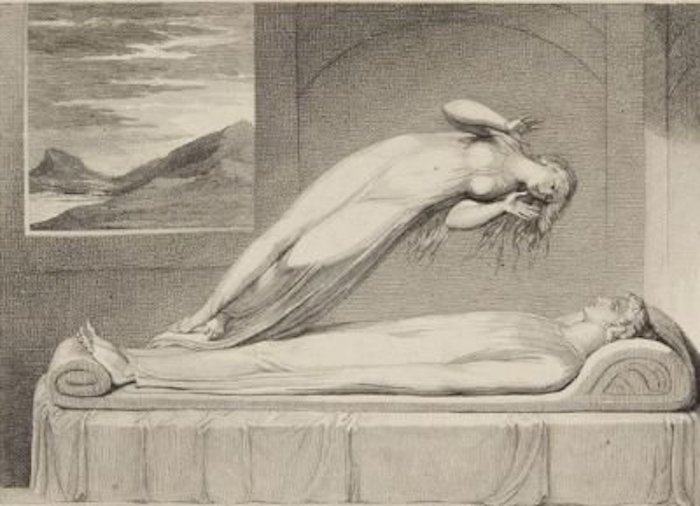

PSYCHICS

Sometimes I used to wake up with moonlight tucked up

to my chin like warm smothering wool

and hear drops of water smash into the bath.

Then, wanting no more sound than the gentle

irritation of water on enamel

I’d leave my bed and turn at the door

to watch myself grunt and roll over.

Astral projection, a pattern

of upbringing no-one can alter,

even a genetic faculty it worked

like a curse not a charm dividing me

from what I felt and was never

exorcised by the cold rinse I had

before going back to the empty bed.

My father endured the gift, too,

telling my mother how he’d struggle

to get back to her and himself

as he drifted above the bed

watching the rope of phosphorescence

which tied him to his navel dwindle

to an almost invisible thread.

And for his father the thread was broken.

Detached, he lived on higher planes

becoming at each remove a vaguer

more omnipotent apparition of himself.

When my grandmother lay haemorrhaging

he left for work to come back ten hours later

and receive the news that she had died.

It didn’t matter. Whether fleshed or ghostly

she was always summoned and embraced

as dream substance. He used his other gifts

to touch the real. In the Great War a voice

guided him through a doorway hot enough

to melt bullets and one when he refereed

a hockey match a player was injured.

He said “I knelt down. The shin was broken.

I could feel the break underneath the skin.

The player was crying with pain.

I knew I had the power so I healed him.

It was strange how all the players

witnessed the miracle and then

immediately forgot it.”

** I wrote this after the return of an adolescent nightmare where I would see myself asleep. My father had similar, but more distressing nightmares perhaps brought on by traumatic experiences in the Second World War and the anecdote about his father’s experience was told to me by grandfather himself.

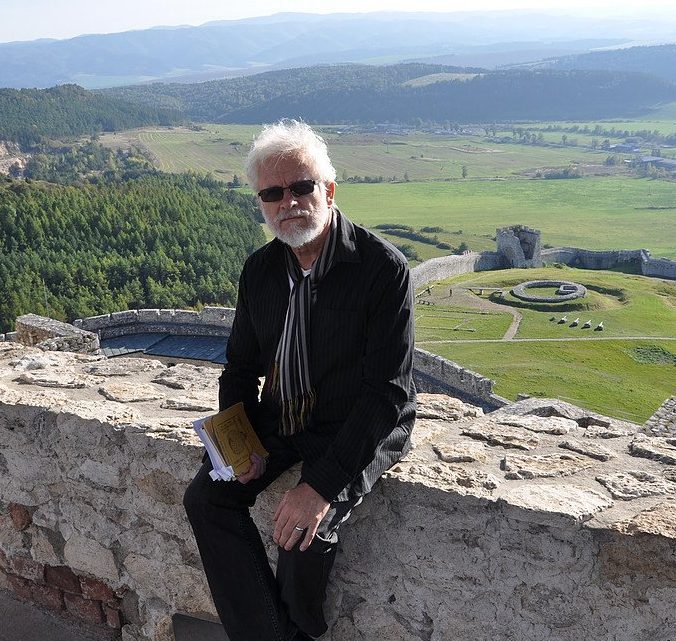

THE FIRST FREE ELECTIONS

The soldiers sitting in their summer kit smell like hay.

A student with a birthmark on her throat like a tiny rose,

Who’s yet to pass even one exam, sips red wine and Pepsi

As she serves behind the bar where there’s a video machine

And election posters – The Party for Drinking Beer,

The Party for Erotic Education – each gained less than one per cent.

A lovely waitress slovens between tables with a rancid cloth,

Black hot pants and a see-through blouse with green polka dots, no bra.

“A reason to return,” you say.

What are we doing here?

Once upon a time there was a girl who was afraid

Of mice and frogs; tall, small-breasted whose walk wouldn’t rustle grass.

I said you ought to be a model with a walk like that,

But you took my straw hat from my head and put it on your own

All the while smiling that it was not your way,

That your good friends, the nuns, so recently proscribed, had said

It was better not to, that kissing any sort of frog

In any sort of way would be disastrous for your health.

Princes would not be your fate, you said.

What are we doing here?

“We’ve got freedom now,” you say. “Perhaps I have to try

Even bad things at least once.” Nothing and no-one in this place looks free

As girls take soldiers by the hand and lead them through a door

Opening on to stairs. The student’s turned the video on

And strange acts, not quite disgusting, take place between half-pretty girls

And sullen men to a mournful theme of Eric Satie’s.

“Will you pay for a room?” you ask. I’m tempted to reply

That this is not my way. But I’m enchanted.

“Of course,” I croak, “Of course. Of course,” not

What are we doing here?

James Sutherland-Smith

His most recent translation was the work of Mária Ferenčuhová also published by Shearsman Books and he is completing a selection of poetry, translated from the work of the Slovak poet, Ivan Štrpka.