- Ravi Zupa

- Douglas Mason1

- Natalya Sukhonos

- Yael Friedman

- Jack Neary

- K. McLeod

- Bob Bickford

- Chris Vaughan

- Chris Robinson

- Lynn Crosbie

- Rosby Strong

- Alana Solomon

- Velvet Chic Volcano

- Douglas Mason

- Suzanne Richardson

- Steve McOrmond

- Charles Wing-Uexküll

- Corey Hardeman

- Eliška Jahelková

- Todd Dixon

- Donnez Cardoza

- Rebecca Blissett

- Lunar Boy from Salem and Cinemascope

- Douglas Mason2

- Gun Roze

- Jane Wilson

- Toby Rosenbloom

- James Sutherland-Smith

- Kathryn McLeod

- Michael Murray

- Josh Patterson

- Anonymous

Queen Kensington

Qué tal, Flaca?

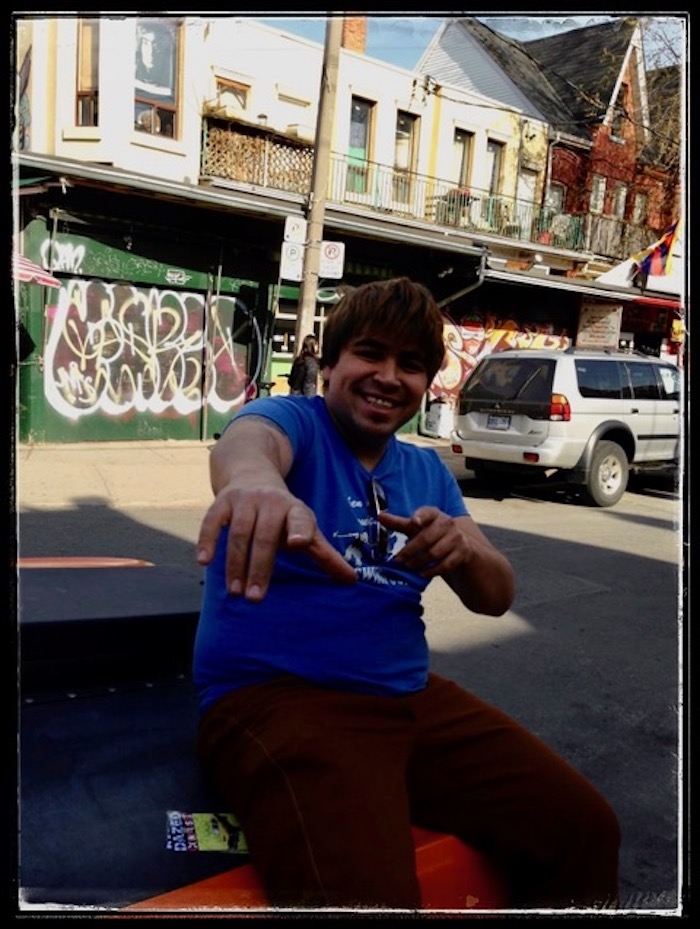

This is Ricky and immediately my eyes vomit tears.

I am am immense woman now, and look like a parade float presenting the

rigours of mental illness.

“Are you making fun of me?” I ask, swiping at the trough of black sludge

beneath my eyes with one fat paw.

“Never, Mamacita,” he says and I lumber toward him, my arms outstretched.

He falls into them and we murmur to each other about our days: his are long,

and punishing—he studies hotel management at night and works as a common

labourer the rest of the time.

Usually, I see him standing with a few other men, each holding their hats and

waiting to be picked up by the man in the El Dorado.

But today, he is free.

I have paid for Ricky’s liberty and intend to sit with him, on this golden afternoon

in early September, at the patio at Ronnie’s, and order one honey-colored ale after

another.

“Whew!” he says, sitting down and fanning himself with his copy of Venganza

des Angeles.

“I’m wiped out.”

I frown. Complaining is not part of our agreement.

Ricky is fast. “But not too wiped out to spend the day with you, mi nińa,” he

says and I shiver.

I am mother and child to Ricky: I am every woman, I think and purse my lips as

he paints them coral.

I extend my hand and he strokes it in small circles, telling me about El Paso,

Texas.

“I feared my father,” he says. “The man had a temper. Even though he only used

it on himself.

Tragic was the day he whipped his own ass for his insolence!”

“How bizarre,’ I say and cough, delicately.

This is my signal to change the subject and speak about me. About what beauty

is still visible, amidst my heft and advancing age; about amazing things I have done or

said, and how good I make him feel.

My haunches tighten.

“Bonita,” he says. “Have I ever told you how magical you are?”

He gestures for another round of the good tequila he is drinking three shots at a

time.

“Why, I’m not sure,” I say, my cheeks pinking.

I lean forward.

“Tell me more,” I say and begin to feel the effects of the sun and the beer, as

Ricky puts together a story in which I, dressed in miles of lace and white satin, appear

to banish the pain from his life; the drudgery.

“You and your little wand,” he says, rapidly smoking something from a cone of

tin foil.

My head is lolling.

Ricky calls over some friends. I buy everyone a round, and Ricky and I double

up our order.

The waiter, a frosty white man with a black conk and full beard, places the bill

before us and I leave him, as a tip, a lock of my hair twined around a two dollar coin.

“So romantic!” Ricky’s friends cry and I smile, bleary-eyed, at them.

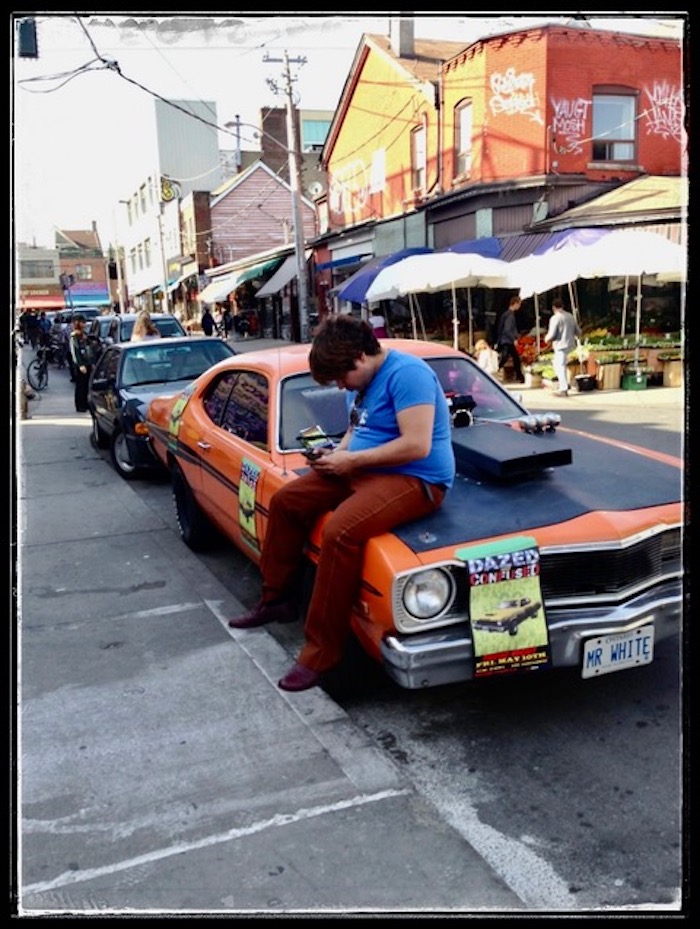

They prod me with sticks on the street to keep me standing, and we stop at

Ricky’s orange GTO that cross-functions as a projector.

“Showing ‘Dazed and Confused’ tonight,” he says and they start singing.

I fall to my knees.

I am hot and sick; my sides ache from the pointed sticks.

“Take me home?” I say, but Ricky shakes his head.

“I’m off the clock,” he tells me.

“Tell me I’m a tiny princess?” I say and everyone laughs.

I look at myself in the window of the fish store.

In my wrinkly black dress, my belly hangs, low and distended; my vast legs end

abruptly at my pink ballet flats.

And my face!

Once gazed into by quivering, radiant boys, it is nothing but a spoiled tomato,

crested with a haze of grey-black hair.

Anger, my oldest friend, comes to my aid.

“Old twink,” I say to Ricky, and he looks away.

“Pathetic shoveler!” I say, backing away and the others begin throwing car

debris.

I am struck with a map of Sioux St. Marie, a pine-scented dangler and balledup, cheesy, foil.

“Chulo sucio,” his friends call me and exchange complicated handshakes.

Ricky is grimly quiet now.

I have traveled half the block as passersby impersonate the sound of a large

truck’s manoeuvres.

“I tried with you,” he says. “I know you’re lonely.”

I can barely hear him, but am filled with wrath once more.

“You tried?” I say.

“I’m like an angel. I am an angel,” I say and beat my chest.

“Walk away,” he says and one of his friends suggests, very loudly, that they

screen the film on my ass.

When I make it to Spadina I stand before an array of trussed, empurpled duck

parts.

To each I say, “Everyone hates me,” as I gulp at the air.

To the proprietor, I say “Ten egg rolls,” and sit down, my rear end swallowing a

stool, and watch the street.

When Ricky drives by I will rush out and throw fortune cookies.

Each one will say I am no good. But I needed you.

My gallant friend will snap them open and smile.

“Until next time?” he will say as I cry with gratitude, and observe, acidly that I

am here for him.

Whenever he needs something.

Lynn Crosbie

Lynn Crosbie is a writer who lives in Toronto and loves herbivores, brunets, fast songs, long walks to the Dollarama and cool whips.

You can follow here on Instagram HERE.