- Ravi Zupa

- Douglas Mason1

- Natalya Sukhonos

- Yael Friedman

- Jack Neary

- K. McLeod

- Bob Bickford

- Chris Vaughan

- Chris Robinson

- Lynn Crosbie

- Rosby Strong

- Alana Solomon

- Velvet Chic Volcano

- Douglas Mason

- Suzanne Richardson

- Steve McOrmond

- Charles Wing-Uexküll

- Corey Hardeman

- Eliška Jahelková

- Todd Dixon

- Donnez Cardoza

- Rebecca Blissett

- Lunar Boy from Salem and Cinemascope

- Douglas Mason2

- Gun Roze

- Jane Wilson

- Toby Rosenbloom

- James Sutherland-Smith

- Kathryn McLeod

- Michael Murray

- Josh Patterson

- Anonymous

On Paper

When a good girl is sick and tired of being good, she will inevitably balance things out by meeting a bad boy. As long as this is all timed right, say around the age of 16, when the confluence of youth and adulthood is still ribboned with some innocence, it usually only results in some scrapes on the soul. It should be pointed out that letting bad boys in at any other point in life is generally a terrible idea. Many of those good girls get spoiled by the fists of alcoholism. A life of standing in the middle of the living room, babe after babe on hip, while furtively glancing at the driveway from between the sliver where the faded curtains meet. These are the stories I’ve heard.

But girls don’t really know this when they’re 16 and bored out of their skulls. Especially if they want more than anybody could ever realize, to shed a musty blanket past of religious oppression. These girls meet bad boys just by chance, usually. Maybe it was by filling out a Valentine’s Day computerized match-making questionnaire at high school, a fundraiser put on by student council. Maybe when the good girl got to the musical preference question, she chose metal even if she didn’t listen to that kind of music much at all. Rebellion in small acts.

When she got the results of her questionnaire back with rows of names and phone numbers, she thoughtfully ran her index finger down the side of the paper, taking care not to rip the path of holes created by the dot matrix printer, as if they themselves were a row of hopeful red hearts. Maybe she didn’t care about the name in first place that was 87.4% compatible with her. Total nerd, she thought. The only name that widened her eyes was the one in fourth at 64.3% because she’d seen that boy around, and she knew him to be wild.

By complete chance, like it was absolutely meant to be because the boy would be kicked out of school within a week, the girl passed him in a school stairway later that day. – Hey, she yelled as he passed. He looked. – We’re a match, she told him. You know, that Valentine’s Day thing. She rolled her eyes when she said thing and then laughed as she walked through the stairwell doors.

The bad boy called the good girl that night. – Hey, he said. Let’s hang out sometime.

He often waited for her after school, lying on the front lawn flicking his butterfly knife with his loose wrist so it caught the sunlight in flashes, like a fish jumping out from his fingers. When he saw the girl appear, he’d jam the knife into his back jeans pocket, run over, and fling her around in a hug. She pretended not to like it, half-heartedly swatting him away. Secretly, though, she did because she wasn’t used to being hugged.

When a different boy, not a bad boy but a stupid boy, broke into her old car to steal the radar detector from the dash, she told herself that it was karma because she bought the radar detector hot in the first place. But the bad boy didn’t believe in karma, only beating people up. He strode into his old school and found the thief packing his binder into his knapsack. The bad boy grabbed him by the neck of his t-shirt and stuffed him into his locker. The bad boy made a further scene of it by thumping the metal locker and screaming threats of atrocities through the vents, so much the thief sardined inside the locker was probably feeling a lot safer there than in the hallway.

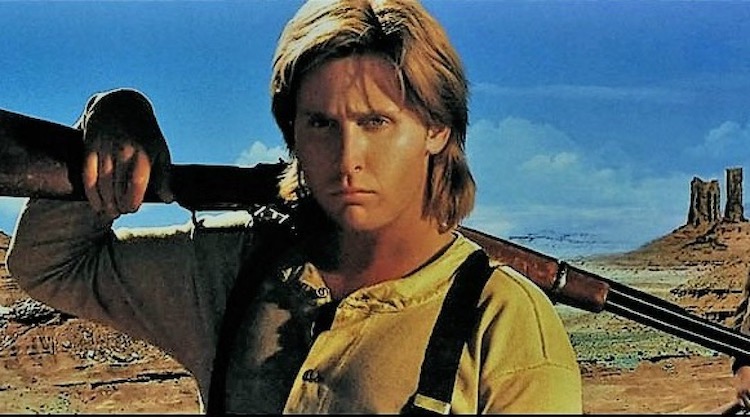

The bad boy liked to spend time at the local arcade down by the beach. The arcade was in a dingy basement of a fancy restaurant. It was decorated with faded movie posters and employed a skinny shift of a man whose shoulders in line with his earlobes. On the wall behind the pool table was a dated poster for Young Guns II; one time, the bad boy was standing directly underneath.

The good girl was so struck by his resemblance to Emilio Estevez in the poster – the same hair and everything! – that she pointed and exclaimed. She meant it as a compliment, but the bad boy didn’t know that. He cracked the pool cue over the table like he was swinging an axe to a stump. The good girl laughed because she was only 16 and didn’t know any better. The skinny man kicked them both out.

The bad boy had a fast old muscle car. Maybe he told the good girl that she could drive it once in a while because he totally and completely trusted her. She did not fear that car, with him beside her. She felt the machine directly through her hands on the wheel and to her heart. It was a living thing and, by extension, she became fully charged. She began driving the muscle car by pushing the gas pedal with her toes, just softly until the car lurched forward. It was much different from her car, where she often pressed the pedal to the floor, and the car would just plaintively sigh.

Soon, with premature confidence, she stamped on the pedal of the muscle car. She wanted to wield power, and she did. The bad boy’s face drained of colour when the car roared and fishtailed down the pavement. The good girl grew so comfortable with its responsiveness, it was the fastest car she’d ever seen let alone driven. One night, the good girl who maybe was driving far too fast chose to ignore the lights of the police car that swung around to follow. She cut down a windy road, killing the headlights – yes, she even spoke in car parlance now – and floored it until she skidded into a hidden driveway. When she shut off the ignition, the bad boy allowed a long exhale through the teeth, not in approval but not in disapproval. Maybe the girl didn’t really care either way as she stared at the rear-view mirror watching for the police car to fly by.

This raised the stakes of some unspoken game. As they often did, the bad boy and the good girl went for a drive one night but this time with two others, a friend of each. The bad boy let his friend drive the car, and the good girl silently reprimanded herself for the feeling of betrayal. It wasn’t as if the car were hers, she reasoned. The bad boy had brought a shotgun along for some reason. As the car raced down the street by the ocean, engine howling, the bad boy rode side-saddle on the passenger door panel, shouldering the shotgun. It wasn’t loaded, but nobody knew. Maybe the good girl slunk low into the back seat, not out of fear but embarrassment.

Still, the good girl treasured the bad boy. Despite never being lovers, they were affectionate towards one another, but never beyond holding hands.

The last time the good girl spent any time with the bad boy was later that summer. It was four of them again, each with a friend. They’d all smoked pot and walked aimlessly along the shore under the silvery moonlight. Eventually there was a divide in the group with the girls walking ahead. – Hey! the bad boy shouted the good girl’s name so she would look back. She did and saw that his jeans were down to his knees. Everything was out, just hanging there. The bad boy laughed. The shadows and the act joined forces to contort his face; shadowy pits for eyes, an exaggerated hole of a mouth. The good girl did not laugh this time because maybe the bad boy finally scared her.

She grabbed her friend’s arm and they ran until they could not run any further.

The bad boy went to the good girl’s house the next day. She saw him pull up and park the muscle car, and by the time she’d stormed out of the front door to confront him, he was leaning against the hood, hands jammed into those jeans of his. – I’m so sorry, the bad boy began. The good girl cut him off – I will never talk to you again.

The good girl did see the bad boy a few years later, on the promenade on the beach. There were lots of tourists, and they were both with groups of friends. The bad boy had tattoos now; they looked like black crescent-shaped slices on his upper arms. He saw her and started towards her; in that same way he always did where she ended up in the air with his arms around her. She turned away. Conflicted, weighing possibilities.

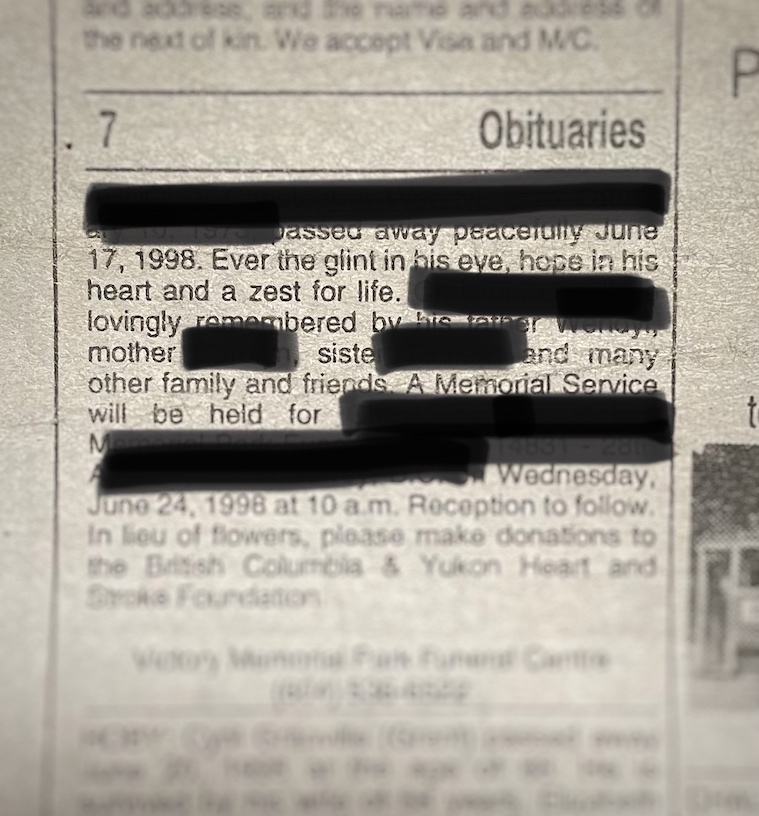

A few years later, still, she saw his name on paper again. Ever the glint in his eye… his obituary read.

Rebecca Blissett is a Canadian writer and photographer. You should buy her forthcoming book Fused.

Rebecca Blissett

Rebecca Blissett enjoys karate, fashion, revenge.

Twitter @rebeccablissett

This excerpt is from her forthcoming book Fused.