- Michael McGrath

- Shawn Micallef

- Jack Neary

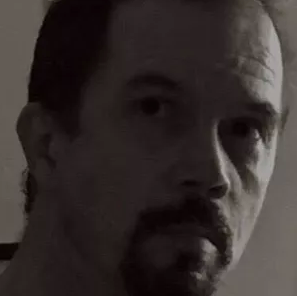

- Bob Bickford

- Camilla Gibb

- Sarah Tsiang

- Corey Hardeman

- Alana Solomon1

- Alf Bogusky

- Anon

- Innes Welbourne

- Tundranaut

- K. McLeod

- Elizabeth Hodgson

- Jim Diorio

- Chris Robinson

- Michael Murray

- Mr. Abbott

- Patrick Vertenten

- Rosby Strong

- Unknown Author

- Eliška Jahelková

- Donnez Cardoza

- Rebecca Abbott

- Will Abbott and Rachelle Maynard

- Gun Roze and Elana Wolff

- Unidentified

- Jane Wilson

- Kathryn McLeod

- Mario Pierre Louis

- Alana Solomon

- William McCann

- Anonymous

Dear Ghost,

I wish it was always summer.

Home from swimming lessons, to sit at the kitchen table for a peanut butter lunch. My mom has her back turned at the counter. Plastic pitcher, packet of unsweetened Kool-Aid, aluminum crack of ice tray. One cube escapes, skitters across the linoleum floor. She swoops and yells at the dogs to leave it alone.

One-two sugar scoops from the bag, then stir with a wooden spoon. We don’t get soda pop, because when you’re all grown up you can drink whatever you like, but not here and not now. Not in this house.

Kool-Aid is the essence of American goodness, homemade with real sugar.

Cherry.

Forget about orange, strawberry, lemon-lime, raspberry, and grape. Summer is cherry, forever.

My mom notices the dogs are wet. They’ve found a place to swim. Nobody wonders where they’ve been—they have their own lives and it’s none of our business. Hands full, she detours on her way to the table, holds the screen door open with a toe and yells for them to get out. They slink past her, three of them, brown and black and white. They’ll be back for dinner. My dad feeds them in the garage.

Paper napkin and grape jelly. It’s too hot for soup.

The window is open and the world outside drifts in. The smells are glorious—melting tar, honeysuckle, pool chlorine, and the electric ghosts of the thunderstorms coming tonight.

I’m going to the library after lunch. The Hardy Boys copy getting returned, “The Mystery of Cabin Island”, sits beneath my green baseball cap beside the front door. My mom yells not to forget my library card, like she always does, so I backtrack upstairs to my room to get it, like I always do. My Sting-Ray looks exactly like a motorcycle, (if someone dropped a motorcycle on the front sidewalk). Iodine and a band-aid on my right knee, and the scrape still stings a little when I swing my foot.

Pine Street to East Fifth to Main, bumping over curbs. In front of the library, I stand on the brake and leave a black mark on the sidewalk, just in case the little girl who sits at the front of my class happens to be passing by. Up the steps, touch the brass Andrew Carnegie letters, then into the dim smell of old paper.

“The Great Airport Mystery” is next. I never read out of order, but I take my time and look at the spines. “The Disappearing Floor”, “The Phantom Freighter”, “The Secret of Pirates’ Hill”. All the good days yet to come. I’m going to climb a tree when I get home and have an hour to read before I start my paper route.

Dear Ghost: Whoever said Heaven is about harps and angels and choirs and clouds and hosannas never went there.

Heaven is July of 1967, a peanut butter and jelly small-town afternoon in Kansas.

One day, I’ll go back. You’ll be sitting at the counter in the drugstore, wearing fresh cotton and sandals, drinking from a straw. The bell over the door will jingle when I go in, and you’ll pretend you don’t recognize me. I’ll pretend I don’t recognize you, either.

You’ll slide a cool glance my way and ask me if I believe in ghosts. Then you’ll laugh your 1940s silver screen laugh. The beautiful sound of you will make me laugh, too.

“What are you drinking?” I’ll ask.

You’ll offer me the straw, and I’ll remember the sweetness before I taste it. Cherry Kool-Aid means I’m home.

Bob Bickford

When I was little the library was my favorite place.I was born in Lone Pine, California. My parents liked to move and so did I, for a while. I have roots throughout the United States, but I was mostly raised in Toronto, Canada.

My father was a psychiatric social worker who grew up in the slums of Boston. He was a tough guy who got an education on the GI bill and pulled himself out of his birthright. He married twice, the first time to a woman who left him a widower. Alone with a toddler, I suppose he was determined that it wouldn’t happen to him again, because the second time he married a woman much younger than he was.

She was the product of a Southern family; royalty that included the same Duke family that bought a university and named it after itself. Wilful and rebellious, she scorned Southern convention, rejected the closeted skeletons and wide streak of alcoholism that hid behind decorated formality. She disowned her family, converted to Catholicism, marched for civil rights, and married the older man from a poverty-stricken background. I am the oldest of the seven children she bore, one after the next.

We were brought up in curious contrasts. There were the economies that so many mouths to feed on a middle class income made necessary; (hand-me-down clothes, Tang and powdered milk, peanut butter for ten thousand consecutive school lunches), but my mother’s background dictated private schools, music and dance and art lessons.

I attended St. Michael’s Choir School and studied piano and organ at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto. I hated studying anything at all; my mother was determined that I should be a doctor and despaired over my future. I only wanted to read fiction, and did so endlessly. The library was my favorite, enchanted place (it still is). I didn’t realize I was in fact studying for what I wanted to do most.

My father’s plan to not be widowed again fell through, and my mother was suddenly gone when I was 16. He had been ill equipped to raise one child the first time, and now there were eight of them; the youngest only three years old. In some sense we lost him, too.

Life changed, just like that. My behavior guaranteed me a quick expulsion from my exclusive school. I did manage a high school diploma (by the skin of my teeth) but I was mostly happy to leave school for good. I lost an early love, and wandered to Los Angeles. I learned about the streets, and about living in the places that cause most people to lock their car doors when they drive through. I was blessed with the same genes that took my father through life in the mean part of Boston, and survived.

Eventually, I grew up and moved again, first to Atlanta and then back to Canada. I made a living in the ‘fixing cars’ arena. I live in a very old house on a wooded lot that is infested by dogs and turtles and parrots, and perhaps the ghost of a young girl. My teen-aged son is a light in my life who wants to be an author and a professional football player. I never tell him that both are nearly impossible, because they aren’t.

The library has continued to haunt me. When age said the possibility of a university degree was long past, I decided to try my hand at a novel anyway. Somehow I finished it, and have produced one a year since. I’m working on my tenth.

You can visit Bob’s Blog HERE.

You can buy Bob’s many books HERE.