- Bob Bickford

- Michael Murray

- David Barry

- P.D. Cardoza

- Robin Gadient

- Yael Friedman

- Kay Murcer

- Corey Hardeman

- Bart Gazzola

- Donnez Cardoza & Bob Bickford

- Chris Robinson

- Kathryn McLeod

- Roberta Rainwater

- Jon Flick

- Clayton Texas East

- Winnie Ramsdell

- Lisa McIvor

- Dale Synnett-Caron

- Lynsey Howell

- Susan Birchenall Gates

- Michael Murray

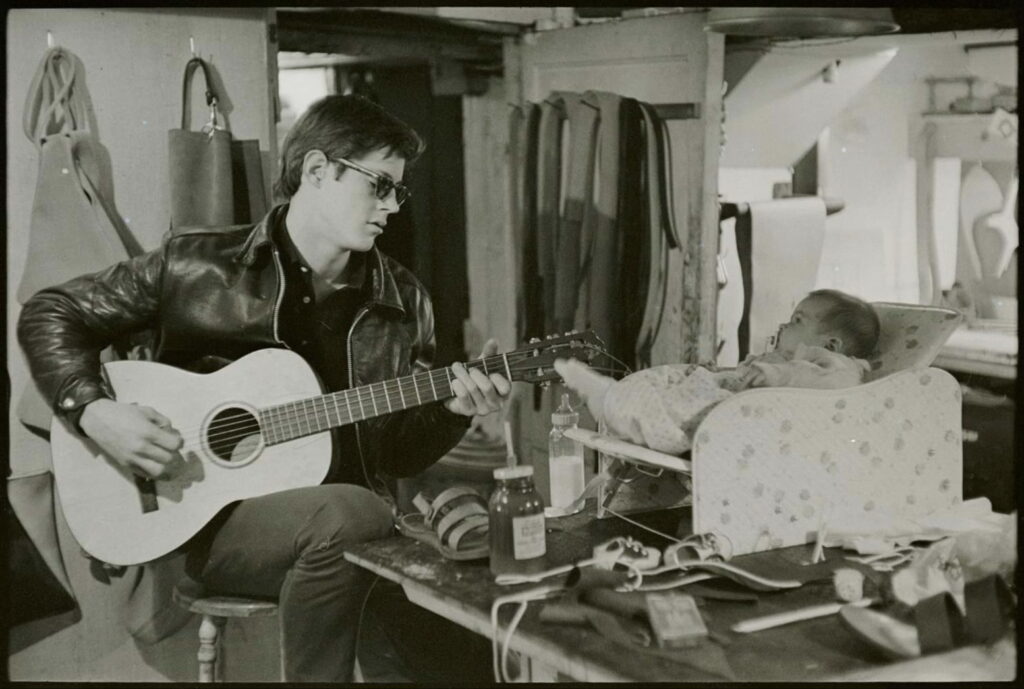

David Barry

Stockton, New Jersey, USA

David Barry in Bruce Britton’s sandal shop, in 1962. Photo by the late Larry Fink

The last time I played with Bob Dylan happened on a beautiful blue-sky day in late August, 1965.

There wasn’t any special musical event planned that day, except I had bought an electric guitar and I wanted Bob to hear it. So, I set out for Woodstock with my friend Art Hogan, a sturdy, untalkative man with a short beard. Art came from Woodstock, but left to find a job in the city. We both ended up working for the same company, Crabtree Movers, which in good times kept enough men on payroll for two trucks. Now it only had one.

I didn’t know Woodstock, though I had been there once. I remember the thrill of the bright green highway signs that took us there on that sparkling August day. Hogan expected to see old friends and I planned to visit Bob Dylan.

Bob and I were pretty good friends.

We first met at a huge bar on Bleecker Street, a bar built to serve everyone at the beginning of the 21st Century. On a bitter night in 1961, it had lost any claim to gentry and became what we called “a bum’s bar.” Bob wore a heavy winter coat and a black gun fighter’s hat. He traveled with a Gibson in a hard shell case—just like me. A Gibson J45.

Now, headed to Woodstock, I didn’t have a clear idea where to find Bob, which started to worry me. I figured I’d ask his manager, who lived there. My break came when we passed three pretty female hitchhikers. One of them recognized Art, called out, and we stopped. A little banter led me to tell them, “I’m going to Dylan’s manager’s house.”

A Black girl laughed and said, “Honey, you don’t just drive up to Albert Grossman’s house.”

My hopes deflated like a punctured balloon, then soared again, since she happened to know Bob was playing pool with John Hammond in West Saugerties, and she knew the phone number. I don’t remember where I called from, but probably a gas station. I picked up the receiver and dialed.

“I’d like to speak to Bob Dylan, please. He’s shooting with John Hammond in the back.”

Bob came on the phone almost immediately. “How you doing, Dave?”

“I’ve got a hollow body electric guitar with me. I’d like to play it with you—see if you like the sound.”

Buying the Gretsch hollow body had a big step for me. I didn’t get it because I wanted to be heard when I played with other instruments. I didn’t play a different style on the Gretsch than I had been playing on my J45.

“Where are you staying?” Bob asked.

“John Hammond’s house, actually. You can tell him I just got here.”

“We’ll be there in a little while. Don’t go anywhere. I have a job for you.”

I had no premonition that the biggest thing in folk music was about to happen right in front of me. I had no clue Bob planned to go electric with his new album, “Highway 61 Revisited.”

We were glad to see each other. Ten years later we might have hugged. Dylan polished his look the same way Willie Nelson probably did at the time. Bob had come to look more like his idol Woody Guthrie. A hard facial contour. The look of a serious, hard-traveling song man, one whose songs reached the hearts of the weary, the down-trodden.

When Bob came into the small room in John Hammond’s house he vibrated with energy. He sat down at the small upright piano and laid down a track that seemed monotonous to me. He didn’t sing. Just hammered out those chords—repetitive, with no suggestion of melody. I played along, with what I could fabricate from those chords. Bob didn’t like my Gretsch’s sound.

“You got a vibrato on that thing?” His voice had already descended into the gritty, growly protest sound that became the favorite voice of record sales in America.

I increased the vibrato, which I didn’t like and never used. I tried to keep the Gretsch sounding as much like an amplified guitar as possible. Bob wanted the sound of all-electric—with every knob turned up to ten.

We didn’t play the monotonous song for very long. Bob had nothing else in the can. I figured I was very much the wrong guy for the job—whatever the job was.

“I’m recording an album the last week of August,” Bob told me. “I’d like you to be there.”

An exciting offer, except for two things—first, a slew of first rate session musicians would likely put me in the shade. I might hang around the edges, but never play a note. Second, the recording was scheduled in the last week of August, right next to the start of college. I knew the risks of putting academia next to a recording session. Something would have to give.

Shortly before the date, I got a stern letter from the dean. I remember his words: Your next try at our college is your last. (I’d already dropped out of Harvard once, to follow the muse.)

I made a choice. I felt certain I would not get asked to play, no matter what Bob said. Plus, I didn’t see a future in the monotonous chords Dylan had played for me.

I turned out to be correct on one count, but stunningly wrong on the other. The musicians contracted for the album included super-session man Al Kooper, and Nashville super session-man Charlie McCoy. All the other backing musicians were lions of the recording business.

I was right to hesitate. I never would have been called out of my chair.

And the wrong? The monotonous chords Bob Dylan had hit on the piano, alongside my Gretsch hollow body guitar, turned into music history. How does it feel?

That song became immortal: Like a Rolling Stone (a complete unknown).

photo credit Donnez Cardoza

David Barry

David Barry

David Barry, known as a stellar guitarist in the early ’60s folk scene, shared coffeehouse stages with Bob Dylan and Maria Muldaur in Greenwich Village. He once offered a young James Taylor a position in his band. He’s played keyboard and ax with the likes of Bonnie Raitt, John Lee Hooker, John Mayall. He was a lifelong friend of Bruce Langhorne (Mr. Tambourine Man). With his guitar, Barry sat in on Janis Joplin’s final recording session in Los Angeles.

All of that happened before he really even got started.

He is ridiculously modest. “It just happened that way. I went out and happened to be in places where things were happening.”