- Michael Harrington

- Lomez

- Tony Martins

- Roobz

- Kayla Alle and Mike Knippel

- Samoa Wilson

- Shelagh Corbett

- Alf Bogusky

- Mr. Abbott

- Rachel Eagen

- Martha Herndon

- Charlie Dalton

- Kathryn McLeod

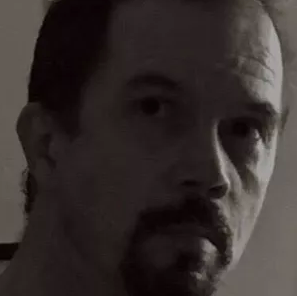

- Bob Bickford

- Michael Murray

- The Galaxy Brains

- Gerard Tevlin

- Leah Modigliani

- Jeffrey Mackie

- Zachary Rombakis

- Jones Murray

- Gun Roze

- Joe Macdonald

- Rob Hyndman

At three o’clock, the phantoms come out. They are antique but oh so young, and they look at each other, eyes wet, and marvel at their own colors.

Toronto city, between summer night and summer morning, and this might be Dupont or Summerhill, with a plumber’s van parked at the curb. Across the street, a church and a lit billboard and the air outside feels cool after the day-heat still trapped upstairs. Behind me, the door lock snicks and it’s final. I can’t go back inside, so maybe I’ll walk up to Eglinton Avenue, and all the sidewalks are empty but they echo with Blondie and white light and spit and orange soda.

Look down to light a cigarette, and I remember the Adidas on my feet—I’ll lose them later on a beach in California in a different darkness, walk home drunk and barefoot—and that loss worries me, even though I don’t know about it yet.

1982 is just a thin skin over tonight, and thousands of miles away and almost forty years in the future a girl-turned-woman looks from a window and remembers where she was right now, and if I remembered her better I’d start walking west and get there when I’m old.

I’m so tired my eyes hurt, but sleep hurts worse and there’s nowhere to sleep, anyway. Tonight the street will take me somewhere if I can find it before daylight traps. Miles to the south, the rides at the lakefront are still spinning colored light and popcorn noise and last year I was there, but now those days are gone and I’m glad I don’t know I’ll never be there again. Some things happen only once.

A bandshell concert, baseball and…

A diner on Davenport Road is dark from the outside, but inside the space is gold and heavy with vinegar mixed with egg-and-cigarettes. They smoke Export ‘A’ Green in this part of town. The place is full, as if the people have all left the street to squeeze inside. The voices are loud and confident, like they have a place to be at this time of night and it’s here, with the bacon and glass ashtrays and little jukeboxes that don’t work—but it’s a lie. They can’t go outside. If they try, they’ll deflate and tumble into nothing, so they’ll stay here forever.

The laughter rises because these people are as scared as I am, of the outside and time—phantom daytime crowds prowling the sidewalks, insisting life goes on—and I’m not that, but I’m not this either, so they watch me.

I ask for coffee, and the woman behind the counter squints and gets a little impatient with my change because she knows I’m not even real. I can’t stay here, with these people, her people, who are long gone. She squeezes the Styrofoam cup into a small paper bag and folds the top closed before she gives it to me. It isn’t coffee for drinking: it’s a cream-and-sugar charm to take with me, a flashlight.

I carry it outside, and smell the city at night.

The cup-in-bag will still be warm in a hundred years, and I’ll still be walking here. A letter’s been riding in my pocket, for a time. St. Clair Avenue is two blocks north and there’s bound to be a mailbox.

That has to be enough, for now.

***Cover photo by Donnez Cardova***

Bob Bickford

When I was little the library was my favorite place.I was born in Lone Pine, California. My parents liked to move and so did I, for a while. I have roots throughout the United States, but I was mostly raised in Toronto, Canada.

My father was a psychiatric social worker who grew up in the slums of Boston. He was a tough guy who got an education on the GI bill and pulled himself out of his birthright. He married twice, the first time to a woman who left him a widower. Alone with a toddler, I suppose he was determined that it wouldn’t happen to him again, because the second time he married a woman much younger than he was.

She was the product of a Southern family; royalty that included the same Duke family that bought a university and named it after itself. Wilful and rebellious, she scorned Southern convention, rejected the closeted skeletons and wide streak of alcoholism that hid behind decorated formality. She disowned her family, converted to Catholicism, marched for civil rights, and married the older man from a poverty-stricken background. I am the oldest of the seven children she bore, one after the next.

We were brought up in curious contrasts. There were the economies that so many mouths to feed on a middle class income made necessary; (hand-me-down clothes, Tang and powdered milk, peanut butter for ten thousand consecutive school lunches), but my mother’s background dictated private schools, music and dance and art lessons.

I attended St. Michael’s Choir School and studied piano and organ at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto. I hated studying anything at all; my mother was determined that I should be a doctor and despaired over my future. I only wanted to read fiction, and did so endlessly. The library was my favorite, enchanted place (it still is). I didn’t realize I was in fact studying for what I wanted to do most.

My father’s plan to not be widowed again fell through, and my mother was suddenly gone when I was 16. He had been ill equipped to raise one child the first time, and now there were eight of them; the youngest only three years old. In some sense we lost him, too.

Life changed, just like that. My behavior guaranteed me a quick expulsion from my exclusive school. I did manage a high school diploma (by the skin of my teeth) but I was mostly happy to leave school for good. I lost an early love, and wandered to Los Angeles. I learned about the streets, and about living in the places that cause most people to lock their car doors when they drive through. I was blessed with the same genes that took my father through life in the mean part of Boston, and survived.

Eventually, I grew up and moved again, first to Atlanta and then back to Canada. I made a living in the ‘fixing cars’ arena. I live in a very old house on a wooded lot that is infested by dogs and turtles and parrots, and perhaps the ghost of a young girl. My teen-aged son is a light in my life who wants to be an author and a professional football player. I never tell him that both are nearly impossible, because they aren’t.

The library has continued to haunt me. When age said the possibility of a university degree was long past, I decided to try my hand at a novel anyway. Somehow I finished it, and have produced one a year since. I’m working on my tenth.

You can visit Bob’s Blog HERE.