- Michael Harrington

- Lomez

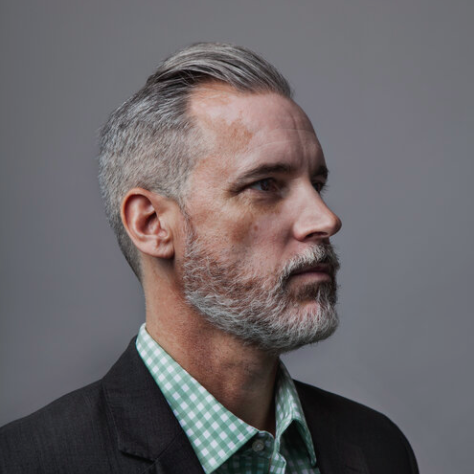

- Tony Martins

- Roobz

- Kayla Alle and Mike Knippel

- Samoa Wilson

- Shelagh Corbett

- Alf Bogusky

- Mr. Abbott

- Rachel Eagen

- Martha Herndon

- Charlie Dalton

- Kathryn McLeod

- Bob Bickford

- Michael Murray

- The Galaxy Brains

- Gerard Tevlin

- Leah Modigliani

- Jeffrey Mackie

- Zachary Rombakis

- Jones Murray

- Gun Roze

- Joe Macdonald

- Rob Hyndman

The night I cheated death in my mother’s white Camaro

What was I trying to prove racing hell-bent, blindly up a hill, in a heavy rain, on an unlit two-lane highway, on the wrong side of the road?

In the summer of 1990, at the age of 24, I drove my mother’s white Camaro across central Canada, from Toronto to Alberta, a 3,400-km trek, to work for two buddies who’d invested in a rickshaw operation in Calgary. I pulled rickshaws for a spell, then ventured northwest to Lake Louise to help manage a pizza joint, then at summer’s end made the return trip to Ontario, this time solo. It was a great summer, but while driving home I was anxious, hurried, and after one particularly reckless incident, lucky to be alive.

The burly Camaro was a 1985 edition with only the base model engine, but it was plenty fast, let me assure you. My mother beamed with pride and delight the day she brought it home, new and unannounced, amazing my sister and I, and causing a stir on our quiet, suburban street.

Mom liked to make flashy, stylistic statements, but in truth the car was not really her thing. She was neither an athletic person nor a ballsy driver. A few years later she more or less handed me the keys when I was half-way through university. It was a long-term loan that I think had been her intent with the car from the outset. She was Scottish and my father Guyanese, but she had a thing for manly Italian men, which partly explains my name, Tony. Now that I was driving the white Camaro, you might have reasonably called me a “Gino.” As a nod to that personage, I adorned the car’s rear-view mirror with a big pair of red, fuzzy dice.

To be clear, I’m no speed demon by nature, but I usually drove the Camaro as it was meant to be driven: quickly and aggressively. On the highway, I had the power to overtake almost anyone and, accordingly, I stuck exclusively to the fast lane. When somebody with an equal or greater machine came along, my competitive juices would kick in like an extra set of cylinders. One time I engaged in a long-distance duel with a silver Saab over probably a 100-kilometre stretch on the 401. We took turns stalking and overtaking until finally one of us had to exit the highway and get on with life.

Those occasional high-speed contests were fun and probably only a little bit dangerous, but the overtaking game I got into with a stubborn driver on the way home from Calgary that summer—that game was downright crazy.

I’d begun the trip back as part of a two-car convoy—my buddy and his girlfriend in one car and me in the Camaro—but we had no navigational plan to speak of and of course no cell phones. When I forged ahead and the cars became separated a mere few hours after departing, there was no way to reconnect.

That meant that for most of the 33-hour drive home, I was alone with my thoughts and fixing to complete the trek as quickly as possible. It was no longer an adventurous road trip westward; it was now a tedious chore. I’d even contemplated driving straight through without an overnight in a motel, but my memory fails and I’m not sure that I accomplished that.

I do remember more generally that as a young adult, I often felt caught. My natural way was to be deliberate and to make decisions slowly, but the world at large wanted me to be decisive and to make decisions quickly, or so it felt. As a compromise, I continued to live mostly without objectives, opportunistically, while waiting impatiently for something to happen, for a door to open, for something to give way. I welcomed change, and risk, and newness, but I couldn’t or wouldn’t go looking for those things. Instead, I would wait for them to find me.

Fate almost found me on my solo return drive that summer, along an undulating stretch of two-lane highway somewhere in Manitoba.

It was a dark and stormy night, for real, and a tiny set of headlights in my rear-view mirror gradually grew larger. The road was wet and the highway was hardly lit so I was driving at what I thought a reasonable rate of speed. The driver of the car now immediately behind me thought otherwise.

When he pulled left and began to overtake, I was mildly pissed off and somewhat alarmed. In these conditions, it was a needlessly risky move, it seemed. What was the hurry? The road was difficult and dark. The wet windshield was messing with depth perception and causing all visible light to flare. Oncoming traffic was difficult to spot.

Despite all this, my feelings changed and pride became a factor when the overtaking car pulled abreast. You see, it wasn’t just any car, it was a station wagon.

A lowly station wagon. A vehicle, yes, far, far below the status and performance abilities of my muscular Camaro.

I scoffed and judged the driver to be an idiot. He must have had the pedal touching the metal to overtake me in a station wagon, I reasoned. The darkness and the thickening rain made it impossible to see inside the other car, which in turn made it easier to imagine the driver as an deluded moron.

He completed his maneuver and on we went, although I immediately hit the gas just enough so that he could not pull away from me. Was this a dick move? Of course it was. My ego was telling me: If he can risk driving that speed, surely you can risk driving that speed.

Then something else must have clicked because I became determined that keeping him close would not be enough. To save face, I had to return things to their natural order.

At the first relatively flat stretch, I made my move. The Camaro had always had a sluggish gas pedal but after a few seconds the power would come in an undeniable surge. My overtake, though certainly dangerous, went without incident and I pulled away, creating a pride-restoring gap between myself and the station wagon, but the game was far from over.

Aside from sluggish acceleration, the Camaro had another performance flaw: is was a heavy car and thus not great at accelerating uphill. Without sufficient momentum, it would lose power during a long ascent. This was a weakness that the station wagon driver would come to exploit.

Patiently, he closed the gap between us. Then, just when we began another extended climb, he got the jump on me and slipped past a second time as the Camaro labored against the effects of gravity.

I shook my head in anger and mild shock. Continuing this at high speeds in these conditions was extremely dangerous, and we both knew it. There was the oncoming traffic problem and there was the skidding off the road to an almost certain death problem.

So what, then, possessed me to immediately prepare for yet another high-risk overtake? Vanity? Boredom? Testosterone? A death wish?

This time, I did not wait for a flat section of road. Like Billy Bishop with the Red Baron in his sights, I began my next assault at what was the beginning of yet another long uphill stretch. I knew it would be long and dangerous maneuver. I thought about the prospect of being torpedoed by an ongoing car. Then I thought “damn the torpedoes!”

What followed was quite possibly the slowest, stupidest, and most hazardous overtake in human history.

I’d built up only a modest head of steam and even with the pedal pressed hard into the floorboard, my progress was slow. I had plenty of time to contemplate that I was now driving full-bore, on the wrong side of the road, virtually blind, in a downpour, uphill, all but asking for a head-on collision.

It must have taken at least a minute, the overtake. For a while we sped along neck-and-neck in a cinematic moment, our tires furiously churning water, windshield wipers thumping in time with our pulse rates, half way up the climb, neither one ceding even a foot of asphalt for the sake of safety or sanity.

My eyes strained at the hill’s crest, scanning acutely for any hint of an oncoming car, half expecting to see a lethal flash of headlights come over the rise, as I slowly, ever so slowly, eked ahead of the stubborn station wagon.

Along with the cars, my heart raced — and an obscure part of me seemed okay with the fact that here and now I might die. How many decent men have been ended by what I was experiencing: the alluring blend of road rage, masculine pride, competitive fire, and the roar of an internal combustion engine?

Finally, after an agonizing and small eternity, my mother’s Camaro won out and order was restored to the roadways. I’d exposed myself to the biggest danger, and prevailed, making me the bigger man, obviously. I edged past the rival driver and scooted over to the right again, to safety, filled with thrill and shame, relieved that fate would need to return for me another day. I would not, after all that huff and puff, die a foolish, violent, too-young death on a remote rain-swept highway far from home.

It’s no surprise that memories of the rest of the drive are mostly blank. I remember only fragments of images of cruising through Kenora, Ontario, I think, and then of mammoth Lake Superior and its glacial waters. I recall marveling at a rural sunset, driving slowly away from my recent failings, breathing, and gazing at the enormous colour-shorn heavens to which I might one day ascend.

Tony Martins

http://tonymartinscreative.space

Tony Martins is a hearing-impaired childhood bed-wetter and three-time failer of the driver’s license road test. You could learn from him! He would happily accept anything donated by readers through the excellent Galaxy Brain site.